Strategy and Governance

|

Contents

1 Introduction

Enterprise information technology (EIT) governance is the established process of defining the strategy for the EIT organization and overseeing its execution to achieve enterprise goals. Strategic planning defines the goals of the EIT organization and communicates those goals as well as how they support the enterprise's goals. EIT governance drives change to achieve those goals, while maintaining agreed levels of operation. Taking into account various perspectives (such as financial, historical, environmental, and future projections), a strategic plan is a roadmap for action and change, both vertically and horizontally, across the EIT organization. The EIT organization's strategic plans are based on the enterprise's strategic plans, focusing on EIT's role in them; EIT governance provides a monitoring and control framework to achieve strategic goals and objectives. Thus, EIT governance is essential for achieving the EIT strategy and goals.

The nature of the enterprise's and EIT's goals and objectives depends on the type, status, and size of the enterprise. For example, the main goal of EIT development for a trading company might be to support the rate of turnover of the warehouse, but for a consulting company the important goal might be ensuring full utilization of all consultants on client engagements.

This chapter provides an overview of EIT strategic planning and governance including the approaches to create an EIT strategic plan based on enterprise strategy, and the role of the EIT architecture.

2 Goals and Principles

Goals

- Achieve a shared EIT and enterprise strategy.

- Achieve a shared roadmap of activities for achieving the shared strategic objectives.

- Monitor and direct activities in order to execute the strategy.

Principles

- Strategy planning selects the right things to do; good governance is doing the right things right.

- A strategy is only as good as its execution.

- Successful execution requires on-going consistent use of metrics.

- What you measure is what you get.

3 Context Diagram

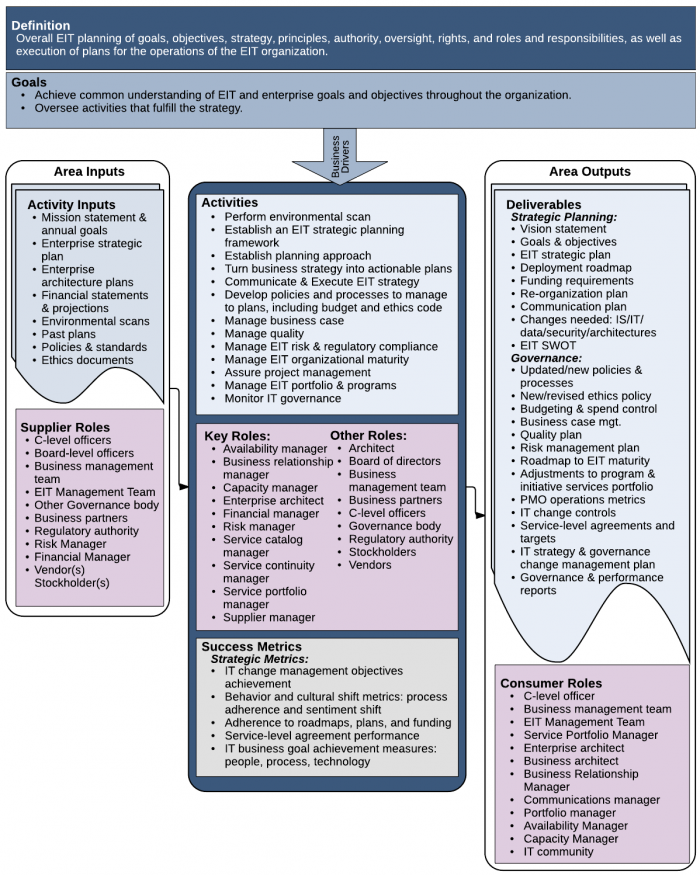

Figure 1. Strategy and Governance Context DiagramEIT strategy is the component of an enterprise strategy that addresses activities designing, building, and managing information and information technology for business change. [1]

While strategic planning occurs at different organization levels, as well as horizontally in many departments, the activity must be coordinated so that there is a hierarchy of strategic plans for each unit of the enterprise that defines how each unit supports the next higher level and coordinates with peers. Although EIT strategy is developed by senior management, it needs to be supported by EIT strategy and goals, standards, frameworks, and guides to facilitate EIT self-governance activities.

Deliverables from the strategic planning process include the strategic plan, the execution requirements, the communication plan, and the socialization plan. They inform a governance framework necessary to deploy those plans in EIT. These deliverables are consumed by C-level executives, and used by business and EIT management and staff to formulate execution plans.

4 EIT Strategic Planning

EIT strategy is a key component of business strategy.

EIT is a business unit within the enterprise. The enterprise's business strategy document is the most significant single input to the EIT strategy document. The business strategy frames the scope and expectations for the EIT strategy. Any supply chain, outsourcing, onboarding, or other EIT practice should be driven out of this strategy. For example, if the business chooses to add vendor relationships, the focus would be on a value stream called an onboard supplier, and capabilities that would include partner management, asset management, agreement management, and related capabilities that are supported by associated EIT capabilities in these areas.

The resulting activities could involve consolidating and improving automation around this value stream and capabilities, as well as numerous other non-technical business activities that may or may not involve systems and technology. Specific topics may include:

- Outsourcing of systems, process, maintenance, technical risk management and transition approaches

- Cloud contracting advice

- Mobile strategies

- Data and information management and integration strategies

- SLA framework strategies

- Logistical and business cultural constraints

- Resource optimization options

4.1 Strategy Mapping

Successful strategy determination and execution needs to be based on a clear picture of the current state and capabilities of the organization as well as a 360-degree view of the environment it operates within. Strategy mapping provides a method for gaining this picture and then articulates a strategy in such a way that it can be readily interpreted and acted on.

- Strategy maps vary, but are essentially graphical depictions of goals, objectives, and related courses of action, often aligned against an organizational and broader environmental backdrop.

- Strategy mapping of the environment looks at shifts in technology in the marketplace, regulatory change for transparency, corporate marketing channels, and competitors' enterprise models.

Strategy mapping depends on a current assessment of EIT systems, capabilities, resources, and EIT maturity.

Strategy mapping has existed in one form or another for some time. Sample strategy mapping approaches that apply to enterprise and EIT strategies are listed below:

- Strength/weakness/opportunity/threat (SWOT) analysis

- SWOT surfaces internal and external perspectives that should be capitalized on or otherwise addressed.

- SWOT findings are one input to strategy formulation providing possible focal points in strategy development.

- The Norton Kaplan Strategy Map [2] links actions to value creation along four dimensions: financial, customer, internal (employees), and learning and growth. The strategy map offers a complete, in-context perspective on the strategy.

- Hoshin Kanri [3] provides similar cross-mapping concepts include tying mission, goals, and objectives with action items, and key performance indicators (KPIs).

- The business motivation model (BMM) [4] provides a mapping between the ends to be achieved (i.e., goals and objectives) and the means (i.e., strategies and tactics) needed to achieve those ends.

Generally, only one approach is selected for a strategy map. Regardless of the approach taken, the end result of any strategic EIT planning process is a clear set of measurable objectives, priorities, and action items that management can act on to deliver change leading to improved EIT performance.

4.2 Blueprints and Models for Strategy Formulation

Blueprints and models provide valuable input to the EIT strategic plan. Typically, few artifacts exist when initiating a strategic planning effort, which means that they must be developed together with business input. The EIT strategy document becomes an extrapolation from the enterprise strategy with an EIT lens.

Enterprise architecture (EA) includes business architecture, which supplies "a blueprint of the enterprise that provides a common understanding of the organization and is used to align strategic objectives and tactical demands." [5] The blueprint includes such artifacts as capability maps, information maps, value maps, and organization maps.

Some other artifacts include operating models, product maps, stakeholder maps, process models, dynamic rules-based routing maps, data models, network models, systems models, vitality and renewal plans, and a wide range of hybrid blueprints and models that have specialty uses based on the challenge at hand.

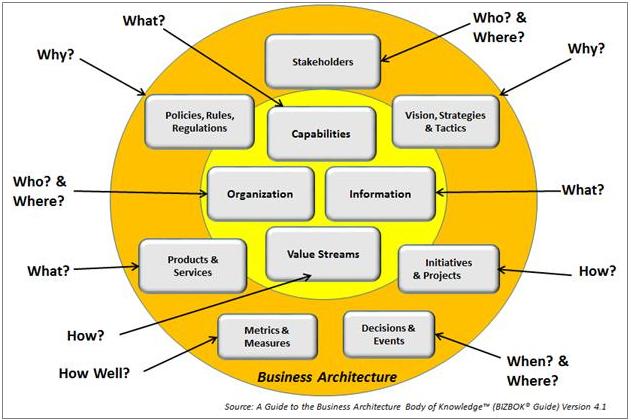

Blueprints and models require consistent, standardized components. These components draw from the abstract representations of the business shown in Figure 2. In the figure, the center circle represents concepts and includes capability, value, organization, and information. These concepts are considered core, because they are very stable business and EIT perspectives that remain relatively constant. Changes occur as required to accommodate business and EIT as they evolve. EIT inherits some of these blueprints from the business and transforms them into aligned, EIT-focused forms.

The yellow circle in the figure shows influencing perspectives. For example, strategies continue to evolve in real time while new business and EIT products and services are introduced routinely. These examples show how the outer circle of business abstractions are more dynamic than the stable core. Collectively, when mapped and presented appropriately, the core and extended views provide a complete and holistic planning view.

Figure 2. Business Architecture Ecosystem [8]Sophisticated blueprint mappings can emerge from the collection of components shown in Figure 2, which represents the business ecosystem. Even simple concepts, like value stream or capability cross-mapping, serve as a basis for business-driven roadmaps and investment planning. Collectively, all of these perspectives answer important questions such as why take action, what is impacted, or how to accomplish a particular task.

4.3 EIT Strategy Formulation

When management has the ability to view the impact of change using these abstractions, everyone from the executives and planning teams to the deployment teams can have a shared perspective of the context and scope of these changes.

For example, consider the goal to provide more customer and transactional transparency throughout the product sales cycle; where "transparency" across the sales cycle means visibility into transaction history and sales potential. Business architects would determine that this strategy targets the acquire product value stream and account file management, customer management, and account routing capabilities. Other enterprise and solution architects would then look at the goal from their delivery perspectives. These perspectives are likely implemented today using a cross-section of technologies and processes, some of which are well understood and adaptive, while others are not. The EIT strategy provides a framework for assessing current state implementations, defining the desired target state, and outlining a series of change initiatives for moving from current to target state.

Drafting an EIT strategy requires alignment with enterprise and business strategies, a good fit with the existing enterprise and EIT culture, a good understanding of EIT capability (including standard practices), and steady governance. While enterprise and business strategies come from business, adherence to agreed upon practices falls within the EIT domain.

The use of standard practices can be difficult when EIT owns numerous systems that were designed and developed in a prior era. These legacy or heritage systems often have associated challenges or issues. These systems are typically developed using older technologies and their architectures often do not conform to modern design principles (e.g., SOA) or to current business needs. Adherence to recommended EIT architecture practices is difficult when architecturally inelegant legacy systems must be updated to accommodate the current business strategy, or when time-to-implement constraints override quality or feature requirements. When such a conflict occurs, the organization begins to build technical debt. (Technical debt is defined as "the negative effects of applying ill-advised or problematic changes or additions to software systems and their data, negatively impacting the delivery of future business value." [6]) In addition, changing business architecture and rules can, over time, lead to data- and information-quality issues. Lack of business alignment and data-quality issues are some of the more difficult and time-consuming issues to address.

EIT proposals for legacy modernization (upgrade or replacement) often neglect to tie these projects to strategic business objectives. Since their costs are often high, these projects can be a hard sell to the business. Any attempt to sell such projects must include the business benefits for continuing to deliver the same functionality as before upon completion of the project. Benefits can include increased speed of transactions, increased reliability, increased interoperability and integration, among others.

The following six-stage framework for EIT strategic planning ensures that the business strategy is integrated into the planning process and that EIT strategy is not driven solely by technological upgrades:

- Craft the EIT strategy and plan to support well-articulated enterprise and business objectives.

- Leverage EA to feed the strategy. Vet various perspectives.

- Highlight EIT focal points for each objective.

- Establish key performance indicators (KPIs) for each strategic enterprise objective and related action item.

- Establish a plan timeline roadmap including a review plan.

- Establish or leverage EIT governance to ensure that business strategy is realized.

The steps in the planning process outlined above should work for most organizations as they embark upon their business and EIT strategy planning efforts. Most of what is needed in strategic planning within EIT is a reflection of the broader context of business planning. Thus, planning for EIT and business scenarios that are essentially the same scenario, such as outsourcing a capability or managing suppliers, should take an integrated, holistic, and enterprise viewpoint.

4.4 Strategic Focus for Change Initiatives

A well-defined EIT strategy provides the roadmap needed for getting from where the enterprise is at present to where it needs to be. The strategy identifies how and where the enterprise needs to change. Strategic planning must determine effective ways to take the enterprise strategy and transform it into EIT strategic change initiatives.

Strategic change employs a wide array of disciplines and techniques to enable change on a large scale as well as on an incremental basis. Change initiatives are frequently defined in the context of types of focuses, such as: [7]

- Governance

- Information/data

- Solution

- Technology

- Security

Each focus has constraints that must be understood and reflected explicitly in the strategy. Constraints almost always include time, quality, and cost. Each focus may also be bounded by organizational scope (such as Western Hemisphere operations only), or by a timeframe (such as a 2-year horizon).The environmental scan may also have recognized other constraints, such as regulatory requirements for the industry. An EIT strategy also acknowledges existing EIT constraints imposed by enterprise architecture (EA), human resources, legacy systems, staff capability, and capacity to deliver.

The organization's appetite for risk may also introduce constraints. The strategic planning effort must take risk into account within the plan. Therefore, the strategic planning effort must also suggest risk responses so as to minimize risk-based constraints. The suggested responses require vetting and approval as part of overall strategy adoption.

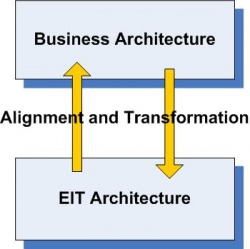

Figure 3. Business Architecture and Continuous Business/EIT AlignmentIn defining change initiatives, it is crucial to recognize that there is a two-way relationship between business architecture and solution, information, and technology architecture, as depicted in Figure 3. A change in either of these aligned layers should be transparent, duly assessed to determine reciprocal impacts, clearly linked to a specific business objective, and addressed through a funded change initiative. Change Initiatives explains how change initiatives are carried out.

When business needs are mapped appropriately to current and future EIT plans, it ensures that business objectives are known, quantified, clearly articulated, and linked to business value. Thus, any EIT investment must show a demonstrable link back to business value. For example, an application change may require significant funding. Architects should be able to trace the planned application changes back to the business capabilities, value streams, and information that the change addresses, and thus back to the business objectives for the proposed change, thus linking the change to business value. In this way, all EIT activities can be tied back to measurable business impacts and business strategy.

The change approval process [9] exercises the authority to introduce change into the EIT environment. It is the responsibility of both the business and EIT. The governance of change management occurs at varying levels of authority depending on the nature of the change. Any proposed change, whether a commissioning of a new system, an application enhancement, a sustainment activity, or corrective action to repair a defect, moves through governance processes.

- Changes may be at the strategic re-alignment level as plans and architecture responses move to adjust projects and programs that are prioritized or in flight, including the possibility of activity shutdown.

- Changes may be at the operational level where a change control board or change advisory board approves code or systems, or data changes into the production environments and can include planned and unplanned (emergency) changes, projects, and releases. Still, such changes should be evaluated in terms of the organization's strategic priorities. Otherwise, there is a risk of wasting resources on asked for, but non-strategic enhancements to less important systems.

- Incidents occurring from change handling activities are reported to EIT governance for possible response particularly if additional funding is required for corrective action. Other incident handling occurs at a more local response level.

- Change patterns are monitored and advice on adjustments to programs and procedures are generated for EIT governance consideration.

5 EIT Strategy Execution

Poor strategy execution is the most significant management challenge facing public and private organizations in the 21st century according to Gartner. [12]

As described in the previous section, any EIT investment must show a demonstrable link back to business value. The link should be tied to a metric that shows the business impact of changes to EIT systems. By establishing a set of essential metrics for assessing the impact of each change initiative, EIT and the business are setting up a valuable mechanism for monitoring the execution of the change initiative, and, thereby, for monitoring strategy execution.

What you measure is what you get. When navigating to a destination, you use a variety of measurements to make sure you're on track to your destination. These include things like estimated time to arrival, distance covered, and signposts encountered along the way. The same holds true when executing EIT performance to achieve strategic goals.

5.1 Effective Governance of Strategy Execution

EIT governance of strategy execution is effective only if cultural and management buy-in are deeply established and consistently demonstrated and communicated. However, that is not enough to ensure success. Reasons for ineffective execution include:

- Performing compliance activities and reporting them without any follow-up review, action, or consequences

- Poorly designed engagement model

- Uneven authority in governance oversight

- Ineffective delegation of authority

- Untimely actioning of governance issues

- Poorly thought out governance metrics (measuring the wrong thing, or encouraging the wrong activities)

- Inaccurate data collection and spotty reporting

- Drifting from the enterprise and business strategies over time so that governance is poorly focused

On the other hand, there are known precepts for successful execution. No matter what EIT strategy an organization decides to adopt, the organization should:

1. Outline the means for achieving desired outcomes, such as:

- Link all EIT strategies to business goals and objectives.

- Specify realistic timeframes and targets that reflect the organizations needs and priorities.

- Create and support a means to generate, capture, evaluate, and implement ideas for improving execution in progress.

- Acknowledge and propose change within known constraints and risks including budgets, staffing capability, and EA plans.

- Implement the strategy into portfolios and projects via change initiatives.

- Create or refer to control processes in organizations that can give oversight to strategy execution. (Are we doing the right things and are things being done right?)

- Create and live a culture of collaboration between the core business and EIT through shared metrics, communications, training plans, and change management support.

- Ensure that the EIT strategy is captured in a living document as a game plan that states measures and targets for strategy achievement and specifies accountabilities.

- Actively monitor and adjust the EIT strategic plan to meet changing business priorities.

2. Ensure full engagement across the business/EIT boundary, by using an enterprise and local interaction model for monitoring, guiding, and reporting. The interaction model seeks to:

- Understand and work through the people side and the organizational side of proposed change and existing culture impacts. This is critical to the long-term success of strategy implementation and oversight (governance) efforts.

- Establish business/EIT collaboration and a communication governance model to ensure open communication and collaboration for business-to-business, business-to-EIT, and cross-EIT perspectives.

- Establish collaborative principles, measurements, and escalation procedures as required.

- Ensure that external regulations and laws, market perspectives, and external perspectives are included.

5.2 Measurement: The Key to Strategy Execution

EIT managers and staff should jointly participate in selecting meaningful metrics to monitor and thus direct internal effort to those activities that provide the "most bang for the buck" in reaching their strategic objectives. The measures and metrics should extend from the lowest hands-on level to the level reported to the board of directors. All of these controls should fit within a hierarchy of goals and their measures.

What this means in simple terms is that you must define discrete goals that can be measured in order to know whether or not an enterprise strategy is being achieved. The measures used to determine if the goals are being met are high-level metrics that are built from lower-level, more detailed metrics. The result is a cross-functional hierarchy of measures. For example, "increase customer satisfaction" is a common goal. How do you know if it is happening? First, determine the components (the attributes) of customer satisfaction. They may range from sales order accuracy to length of time to reach customer support to billing accuracy. All of these can have a technology component as well as a business component. The hierarchy of goals and measures will thus need to include both business unit goals as well as EIT goals, with corresponding metrics.

COBIT 5 describes this hierarchy as a cascade of goals and provides examples of 17 generic enterprise goals related to corresponding EIT goals. The 17 goals are grouped in the Balanced Scorecard categories of Financial, Customer, Internal and Learning, and Growth dimensions Each of these 17 requires further breakdown into attributes of each goal and how to measure the presence of those attributes. For example, one goal is service continuity and availability. Often, these goals have finer goals like allowable mean time before failure (MTBF) and required up-time, and these goals are documented in service level agreements (SLAs) or operations level agreements (OLAs) that specify corresponding metrics, like a 100 hours MTBF or 99% up-time.

6 EIT Operational Governance

EIT governance extends beyond strategy formulation and execution. It must of necessity guide and monitor all the day-to-day activities that serve the enterprise. EIT organizations that are constantly fighting fires, giving them no time to carry out change initiatives, are poorly governed. Governance of day-to-day operations must be well-governed and run smoothly to provide time and expertise to carry out new work.

Businesses with superior EIT governance record 25 percent higher profits than those with poor governance. [10] This type of positive value assessment for EIT governance is well established and clearly maps to EIT governance objectives of a reliable, trusted, responsive, and evolving EIT synced to business plans and needs.

Superior governance leads to superior performance. Superior performance is about doing the right things; it's not about putting in more hours, it's about prioritizing, planning, and executing the most impactful work. Good leadership provides clear direction on where the business is going and how to overcome the challenges that arise. Setting a clear direction not only gets people on board but also builds confidence in the organization's abilities to get results.

EIT governance includes the processes through which the organization's objectives are set and pursued in the context of the enterprise's social, regulatory, and market environment. Governance mechanisms include monitoring the actions, policies, practices, and decisions of EIT personnel, and affected stakeholders. EIT management must make sure that EIT processes, mechanisms, and accountabilities provide the organization with the capability to carry out all its areas of responsibility, such as reporting against budgets, project performance, service management, and risk assessment and management.

Good leadership makes sure that the processes used to get things done are effective in facilitating work, not impeding it. Such processes are transparent and well-understood, so they help people get their jobs done. They are the foundation of EIT governance.

Good leadership and good governance also depend on well-communicated policies whose values and purposes are understood. Policies often reflect an organization's culture. A policy can let people know it's OK to bring their dogs to work, or that people are entitled to a day off with pay for their birthdays. They let people know what sorts of behavior are expected and what the organization values.

6.1 Operational Assessment

Good governance depends on a thorough understanding of the organization's operational status. There are two basic ways to accomplish this. A well-run organization will have a good metrics definition and collection process in place so that managers can monitor their functions' performance in real-time. Less mature organizations often have to depend on point-in-time assessments to know the true state of affairs.

EIT assessments are a point-in-time type of monitoring that supplement the regular monitoring and reporting process. Maturing organizations often do self-assessments. When done by people outside the organization, they are often seen as audits. Some topics that an audit may cover include:

- Return on investment (ROI)

- Data quality

- Inventory accuracy (licenses, software, hardware in use/owned)

- Process performance, rationalization, adherence to policies

- Security effectiveness

- Maturity assessment and reassessment

- Regulatory requirements adherence

The resulting reports include gaps found and remediation recommendations.

The effort and cost to establish and operate EIT governance can be scaled to meet the strategically sensitive areas for the overall organization. Business and EIT share the EIT governance responsibility, because the business must communicate its needs to EIT and its satisfaction with EIT services. Good governance requires exceptional leaders who can communicate across business and EIT subject domains.

6.2 Financial Management

EIT management must plan for all needed EIT resources in its budgeting, including on-going operations, change initiatives, and growth plans. These resources to be budgeted for include salaries and overhead for personnel, training and professional development, licenses and leases, as well as new acquisition of outside services and material assets, contract management with vendors including outsourcing, licensing, SLA, OLA, and cloud computing. Project resourcing also need to be taken into account. (See the Acquisition chapter).

Assets represent value, not just cost, to the organization. That value should be tracked and reported for tax purposes, such as depreciation reporting. While assets are not always included on balance sheets, they must be considered at the time of an acquisition, merger, or liquidation.

Sometimes cost control can be an important, overriding priority that limits EA visions and plans for the overall EIT system evolution. However, such short-term thinking can be at the risk of mounting technical debt or even stand in the way of strategic projects. A better approach is cost management.

Cost management includes careful application of strategies, such as:

- Infrastructure allocation/management

- Application rationalization

- Device and data access policies

- Process assessment (identification of wasted effort)

- Application lessons learned

- Feedback loops

- Process improvement/re-engineering

- Licensing re-negotiation

- Various outsourcing initiatives

6.3 Quality Management

Quality management [12] is a key control in EIT governance. The importance of high levels of quality throughout the EIT organization's actions, services, and products is manifested across all policies, processes, and procedures. There are two basic ways of approaching quality. The first is to take a passive approach; in effect, to adhere to the idea that quality is "baked in" to the organization through the policies, processes, and procedures, and where quality controls are established as an output measurement, much like in manufacturing environments. The second approach is more active, setting out a separate responsibility for quality that establishes responsibility and accountability, checks adherence, and advises and reports on quality risks and failures at many points along work streams.

The adoption of accepted practices given in standards and frameworks is an indication of a more mature organization requiring active quality management as part of overall EIT governance. For example, ISO Standard 9001 applies to any organization that:

- Needs to demonstrate its ability to consistently provide product that meets customer and applicable statutory and regulatory requirements.

- Aims to enhance customer satisfaction through the effective application of the system, including processes for continual improvement of the system and the assurance of conformity to customer and applicable statutory and regulatory requirements.

Several other ISO and IEEE standards provide guidelines for quality management within an EIT organization. See the Quality chapter for information on these.

Monitoring and performing impact analysis of regulatory and changes in industry standards is also a quality management activity shared with legal departments and enterprise architecture.

An organization can address the risk of damage to its reputation and potential fines due to information leakage and misinterpretation by adopting strong data quality-assurance practices within a data-governance program. [15]

6.4 EIT Risk Management

EIT policies, standards, and processes should include explicit sections on risk tolerance and EIT's approaches to risk management including EIT security policy, EIT governance policy, EIT financial management policy, data privacy and classification policy, disaster preparedness policy, supply chain management, vendor management, employee ethics, and regulation adherence policy.

Risk management [16] in EIT involves the following activities:

- Risk identification—Relevant EIT risk profiles on systems are specified. Types of risks are financial, reputational, regulatory (projected and current), security, EIT disaster, market innovation speed, and supplier performance.

- Risk evaluation—All identified risks are evaluated for their severity and likelihood.

- Risk response—Response plans are generated for the most severe and likely risks. Generally, the response is either to accept the risk and do nothing because likelihood or organization concern is low, to accept the risk and plan contingencies for the occurrence, or to transfer the risk to a third party via insurance.

6.5 EIT Maturity Management

The maturity of EIT functions [17] directly relates to the ability to provide a consistent level of business support as well as to execute the EIT strategy. Therefore, there is a need to assess maturity as an input to a realistic plan and as a guide to maturing EIT to desired levels. In other words, unless the EIT organization understands its own capabilities and its own shortcomings, it can't make effective plans to take on more work or to otherwise improve.

Some principles in mounting and actioning maturity assessments are:

- Business and EIT culture and interaction are key elements to capability and performance and cannot be ignored in an evaluation.

- Outputs of the maturity analysis are direct inputs to planning and the strategy plan execution roadmap.

- The adoption of lessons learned is a key improvement strategy.

Improvements will necessarily require changes, so change initiatives should be defined for these activities and executed and monitored as projects. Projectizing such efforts also enables reality checks on the goals and timing to the desired objectives as materialized through EIT change initiatives. (See also Change Initiatives).

6.6 Service Management

Service management [19] in EIT encompasses the full system lifecycle support from concept to deployment and retirement. The most widely known "recommended practices" for service management are described in the ITIL framework and reflected in ISO/IEC/IEEE standard 20000. These references provide guidance for designing and implementing control structures within the EIT governance framework including:

- Service strategy—see the EIT Strategic Planning section

- Service design—see the Enterprise Architecture, Requirements, and Construction chapters

- Service transition—see the Transition into Operation chapter

- Service operations—see the Operations chapter

- Continual service improvement—measurement, monitoring, reporting including monitoring for compliance, financial performance, monitoring customer, and employee satisfaction

6.7 Project Management

Project management [20] is required for all change initiatives in EIT including new services or equipment deployment, enhancements/upgrades to existing services, and significant operations changes. These include traditional EIT activities as well as supporting activities such as communications and human resources.

The PMI/IEEE Software Extension to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK) is an extensive reference that addresses both agile and plan-driven projects. It describes project-level controls that can be adjusted to the level appropriate for the scale of the work. Required project-level controls include defining quality, cost, deliverables, risk, and schedule expectations, as well as process to be used, and authorities for decision-making.

- Good EIT governance ensures that the adequate resources (including staff, training, equipment, and funding) are available when needed. EIT governance works closely with vendors, project managers, financial management staff, and suppliers to achieve these aims.

- Medium-sized and large EIT organizations typically establish a project management office (PMO) to support projects, provide management guidance, and assist in reporting status. This formal oversight body is set up to instantiate common project management practices and reporting consistency across projects. In some organizations, PMO scope is limited to "large projects" (those projects holding significant risk to the organization, and significant cost). This approach usually ends up with the same pitfall: more and more projects are defined as "small" and more and more of them fail to meet cost or feature or schedule expectations.

6.8 Portfolio and Program Management

EIT portfolio management is the application of systematic management to the investments, projects, and activities of Enterprise information technology (EIT) departments.

Portfolio management enables high-level views of all capabilities provided by EIT so that new work proposals can be evaluated against the portfolio as a whole. EIT portfolios may have defined aggregate subsets. An aggregate subset is a set of scoped applications and systems that are closely interrelated; for example, the accounts payable, accounts receivable, and ledger production in an organization. In some instances, the organization creates the role of portfolio manager. Portfolio managers work closely with project managers, architects, operations managers, and business users to make sure that the relationships and the understanding between the business and EIT are strong and transparent.

Programs can span portfolios as multi-phase, multi-year initiatives. Project and portfolio grouping allows for more holistic views on change, impact analysis and synergies, business case development, upgrading, operations problem identification, communication and recovery, vendor and business relationship management, and multi-project oversight. Programs can span multiple systems and often have their own multi-year separate organization structure and board-level oversight.

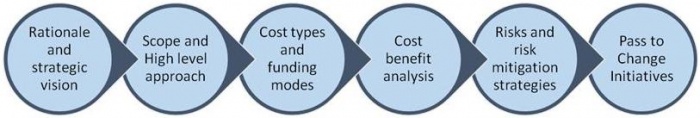

In budgeting for all EIT activities, their value to the enterprise must be evaluated. So called "support activities" are no exception. All proposed efforts should be evaluated through a common lens and should use a standard funding process, as shown in Figure 4. This approach enables the EIT organization to escape the problem of 80% of its resources being allocated to "maintenance," because it forces business and EIT management to examine the cost-effectiveness of sustaining all old systems—regardless of value to the business strategy—rather than adding new services.

Two types of discipline are required: (1) using business cases to evaluate proposed new work, and (2) ceasing to treat enhancement requests on a piecemeal basis, because they are "too small" to worry about. (For details see the section about managing change requests in the Operations chapter).

Figure 4. Steps in Business Case DevelopmentWork is prioritized and moved forward into the realization phase based on the business and EIT strategic plans. The Change Initiatives chapter describes how new projects are treated as change initiatives in order to be successful. The process is monitored for continuing business alignment and need, and considers feasibility factors, stakeholder interest, resourcing opportunities, competitor activity, new EIT tools and approaches, and government requirements in the industry in evaluating proposals for both enhancements and new services.

7 EIT Governance Reporting

Governance reporting is meant to help managers keep an eye on strategic themes, identify potential areas for improving processes, and recognize early on when projects are at risk. It can help managers determine when to offer opportunities for supported learning and improvement in underperforming areas.

However, governance reporting is only useful when it is reporting progress against goals and milestones, and when the consumers of the reports have the necessary authority to take appropriate action and are accountable to do so. Appropriate accountability can ensure that active oversight is in place to handle possible performance issues, including penalties to third parties. (With regard to third parties, also see the Acquisition chapter.)

Effective reporting has the following characteristics:

- A hierarchy of goals (including SLAs and OLAs) and measures is defined for monitoring achievement of strategic goals at all levels of management, including team leaders.

- Weekly reports provide current results for goal measurement. Weekly reports do NOT consist of "this is what we did this week," without reference to what goals are supposed to be tracked.

- Weekly reports include issues (actual and potential) that have arisen. Leaders use a feedback or action model to ensure that issues are addressed quickly. Review and remediation actions are authorized at the appropriate level.

- Typical EIT governance reporting consists of reports up the chain to C-level officers or to the top-level leaders of the accountable steering committee, oversight committee, or operations committee.

Metrics and measures standardize the reports to allow the tracking of progress over time. (A measure quantifies something, such as miles. A metric is a derivative of measures, such as miles per hour.) Some metrics can be characterized as key performance indicators (KPIs), which are of special significance to EIT and business as they are considered to best support the highest priorities. KPIs are financial and nonfinancial measures of the results of a business' strategic plans. A KPI is a reflection of the degree to which an outcome is achieved. A KPI may be directly measured/assessed, or it may be derived from a metric, other KPIs, or combination of metrics and KPIs. For example:

- Error rate is a quantitative KPI composed of two metrics, an error count and a time interval.

- Customer satisfaction is a qualitative KPI that may be composed of a number of metrics and KPIs, such as return purchases and the results of surveys.

Generally, effective reporting includes:

- Progress reporting:

- Adherence to action plan (activities) and funding (budget versus actuals)

- Goal achievement measures (for example, to show progress against the balanced scorecard)

- Execution plan achievement

- Organization changes and their effect

- Financial position trending and forecast

- Problem tracking, such as outstanding trouble tickets

- Emergency preparedness/disaster drills results

- Quality scorecard for SLAs and OLAs, and for development projects

- Metrics that are well-defined and used consistently so that trends can be detected over time

- A clearly defined purpose of each metric, defined in terms of what insights it reports; that is, what is being measured and why

8 Summary

According to Michael Porter[11], more than 80% of organizations do not successfully execute their business strategies. He estimates that in over 70% of these cases, the reason was not the strategy itself, but ineffective execution. Poor strategy execution is the most significant management challenge facing public and private organizations in the 21st century according to Gartner[12]. What good does it do for an organization to have a well-considered strategy that it cannot execute? Such a scenario, which is all too common according to Porter, has a dual downside. The organization will fall further behind the competition and sub-optimize resources and revenue opportunities. But that same organization will spend significant capital on failed projects that can undermine confidence with customers and investors in the management team and the organization as a whole. This is not a good position to be in and, therefore, organizations must determine effective ways to take business strategy and make it actionable.

Important idea to take away from this chapter are:

- Recognize that enterprise strategy drives EIT strategy.

- Understand your purpose for creating an EIT strategy.

- Understand current EIT operations.

- Plan for working on the things that matter to enterprise.

- Take a multi-year perspective, and revisit the plan on a periodic basis for confirmation or changes.

- Enable reliable, nimble, and efficient response to changes in strategic objectives.

- Plan for flexibility and change in governance structure, accountability, and priorities.

- Measure progress and performance against the strategic roadmap as well as on a project and operations basis.

- Enable change, even to the plan itself, as required.

- Advise and align subordinate EIT strategic plans into an overall framework for delivery.

- Continually foster communications and understanding between EIT and enterprise.

- Set expectations within a code of ethics framework.

- Foster a continuous learning organization.

- Look ahead for continuity planning as part of risk management planning.

Good governance consists of good processes and actions in making and implementing decisions. Strategy and its clear goals provide the yardstick for making decisions. Good governance has several characteristics that underpin all the governance areas described above. These characteristics include well-understood meeting procedures, service quality protocols, management conduct, role clarification, and good working relationships, all of which contribute to the hallmarks of effective EIT governance: accountability, transparency, participation, and ethical behavior.

9 Key Maturity Frameworks

Capability maturity for EIT refers to its ability to reliably perform. Maturity is measured by an organization's readiness and capability expressed through its people, processes, data, and technologies and the consistent measurement practices that are in place. See Appendix F for additional information about maturity frameworks.

Many specialized frameworks have been developed since the original Capability Maturity Model (CMM) that was developed by the Software Engineering Institute in the late 1980s. This section describes how some of those apply to the activities described in this chapter.

9.1 IT-Capability Maturity Framework (IT-CMF)

The IT-CMF was developed by the Innovation Value Institute in Ireland. This framework helps organizations to measure, develop, and monitor their EIT capability maturity progression. It consists of 35 EIT management capabilities that are organized into four macro capabilities:

- Managing EIT like a business

- Managing the EIT budget

- Managing the EIT capability

- Managing EIT for business value

Each has five different levels of maturity starting from initial to optimizing. The three most relevant critical capabilities are IT leadership and governance (ITG), strategic planning (SP), and benefits assessment and realization (BAR).

9.1.1 Leadership and Governance Maturity

The following statements provide a high-level overview of the IT leadership and governance (ITG) capability at successive levels of maturity.

| Level 1 | IT leadership and governance are non-existent or are carried out in an ad hoc manner. |

| Level 2 | Leadership with respect to a unifying purpose and direction for EIT is beginning to emerge. Some decision rules and governance bodies are in place, but these are typically not applied or considered in a consistent manner. |

| Level 3 | Leadership instills commitment to a common purpose and direction for EIT across the EIT function and some other business units. EIT decision-making forums collectively oversee key EIT decisions and monitor performance of the EIT function. |

| Level 4 | Leadership instills commitment to a common purpose and direction for EIT across the organization. Both the EIT function and other business units are held accountable for the outcomes from EIT. |

| Level 5 | EIT governance is fully integrated into the corporate governance model, and governance approaches are continually reviewed for improvement, regularly including insights from relevant business ecosystem partners. |

9.1.2 Strategic Planning Maturity

The following statements provide a high-level overview of the strategic planning (SP) capability at successive levels of maturity:

| Level 1 | Any EIT strategic planning that exists or resources allocated to it are informal, and opportunities and challenges are identified only in an ad hoc or informal way. |

| Level 2 | An EIT strategic planning approach is emerging. Limited resources are made available for EIT planning purposes. An EIT strategy is beginning to be formalized, but may not yet be adequately aligned with basic business needs. |

| Level 3 | The EIT strategic planning approach is standardized. Sufficient EIT resources are allocated to EIT strategic planning activities. The EIT strategy is developed increasingly in consultation with planners from other business units to satisfy a wider array of business needs. |

| Level 4 | The EIT strategic planning approach is an integral part of a wider organizational planning processes. Dedicated resources from the EIT function and other business units are allocated to EIT strategic planning, enabling the EIT strategy to comprehensively support and influence the business strategy. |

| Level 5 | The EIT strategic planning approach is reviewed and improved using process improvement methods and tools. A strong symbiotic relationship exists between the EIT and business strategic plans to such an extent that it can be difficult to distinguish between them. |

9.1.3 Benefits Assessment and Realization Maturity

The following statements provide a high-level overview of the benefits assessment and realization (BAR) capability at successive levels of maturity.

| Level 1 | The organization typically focuses on delivering to technical project criteria, such as delivering on time, to budget, and to specification, rather than on realizing business benefits. Post-implementation reviews to evaluate the organizational benefit are rarely conducted. |

| Level 2 | Some larger EIT-enabled change programs are beginning to use limited forms of benefits management methods. Post-implementation reviews are occasionally conducted, mainly to evaluate technology deployment efficiency. |

| Level 3 | Most programs are described in terms of business value and consistently use benefits management methods. Post-implementation reviews are conducted on most programs, including an evaluation of the organizational changes needed to realize the value of technology deployment. |

| Level 4 | The organization has developed deep expertise in applying benefits management methods, and responsibility for realizing value is spread across the organization. Business value reviews are conducted throughout the investment lifecycle, from conceptualizing to deployment to eventual retirement. |

| Level 5 | Management continually monitors, reviews, and improves benefits management methods across the organization, and exchanges insights with relevant business ecosystem partners. Post-implementation reviews of EIT-enabled change consistently contribute to better subsequent use of resources. |

10 Key Competence Frameworks

While many large companies have defined their own sets of skills for the purposes of talent management (to recruit, retain, and further develop the highest quality staff members that they can find, afford, and hire), the advancement of EIT professionalism require common definitions of EIT skills that can be used not just across enterprises, but also across countries. We have selected three major sources of skill definitions. While none of them is used universally, they provide a good cross-section of options.

Creating mappings between these frameworks and our chapters is challenging, because they come from different perspectives and have different goals. There is rarely a 100 percent correspondence between the frameworks and this Guide, and despite careful consideration, some subjectivity was used to create the mappings. Please take that in consideration as you review them.

10.1 Skills Framework for the Information Age

The Skills Framework for the Information Age (SFIA) has defined nearly 100 skills. SFIA describes seven levels of competency that can be applied to each skill. Not all skills, however, cover all seven levels. Some reach only partially up the seven step ladder. Others are based on mastering foundational skills, and start at the fourth or fifth level of competency. It is used in nearly 200 countries, from Britain to South Africa, South America, to the Pacific Rim, to the United States. (http://www.sfia-online.org)

| Skill | Skill Description | Competency Levels |

|---|---|---|

| EIT governance | The establishment and oversight of an organization's approach to the use of information, digital services and associated technology. Includes responsibility for provision of digital services; levels of service, and service quality that meet current and future business requirements; policies and practices for conformance with mandatory legislation and regulations; strategic plans for technology to enable the organization's business strategy; transparent decision making, leading to justification for investment, with appropriate balance between stakeholder benefits, opportunities, costs, and risks. | 5-7 |

| Enterprise and business architecture | The creation, iteration, and maintenance of structures such as enterprise and business architectures embodying the key principles, methods, and models that describe the organization's future state, and that enable its evolution. This typically involves the interpretation of business goals and drivers; the translation of business strategy and objectives into an "operating model"; the strategic assessment of current capabilities; the identification of required changes in capabilities; and the description of inter-relationships between people, organization, service, process, data, information, technology, and the external environment.

The architecture development process supports the formation of the constraints, standards, and guiding principles necessary to define, ensure, and govern the required evolution; this facilitates change in the organization's structure, business processes, systems, and infrastructure in order to achieve predictable transition to the intended state. | 6-7 |

| EIT strategy and planning | The creation, iteration, and maintenance of a strategy in order to align EIT plans with business objectives and the development of plans to drive forward and execute that strategy. Working with stakeholders to communicate and embed strategic management via objectives, accountabilities, and monitoring of progress. | 5-7 |

| Information management | The overall governance of how all types of information, structured and unstructured, whether produced internally or externally, are used to support decision-making, business processes, and digital services. Encompasses development and promotion of the strategy and policies covering the design of information structures and taxonomies, the setting of policies for the sourcing and maintenance of the data content, and the development of policies, procedures, working practices, and training to promote compliance with legislation regulating all aspects of holding, use, and disclosure of data. | 6-7 |

| Information systems coordination | Typically within a large organization in which the information strategy function is devolved to autonomous units, or within a collaborative enterprise of otherwise independent organizations, the coordination of information strategy matters where the adoption of a common approach (such as shared services) would benefit the organization. | 6-7 |

| EIT management | The management of the EIT infrastructure and resources required to plan for, develop, deliver, and support EIT services and products to meet the needs of a business. The preparation for new or changed services, management of the change process, and the maintenance of regulatory, legal, and professional standards. The management of performance of systems and services in terms of their contribution to business performance and their financial costs and sustainability. The management of bought-in services. The development of continual service improvement plans to ensure the EIT infrastructure adequately supports business needs. | 7 |

| Financial management | The overall financial management, control, and stewardship of the EIT assets and resources used in the provision of EIT services, including the identification of materials and energy costs, ensuring compliance with all governance, legal, and regulatory requirements. | 6 |

| Portfolio management | The development and application of a systematic management framework to define and deliver a portfolio of programs, projects, and ongoing services, in support of specific business strategies and objectives. Includes the implementation of a strategic investment appraisal and decision-making process based on a clear understanding of cost, risk, inter-dependencies, and impact on existing business activities, enabling measurement and objective evaluation of potential changes and the benefits to be realized. The prioritization of resource utilization and changes to be implemented. The regular review of portfolios. The management of the service pipeline (proposed or in development), service catalog (live or available for deployment), and retired services. | 7 |

| Program management | The identification, planning, and coordination of a set of related projects within a program of business change, to manage their interdependencies in support of specific business strategies and objectives. The maintenance of a strategic view over the set of projects, providing the framework for implementing business initiatives, or large-scale change, by conceiving, maintaining, and communicating a vision of the outcome of the program and associated benefits. (The vision, and the means of achieving it, may change as the program progresses). Agreement of business requirements, and translation of requirements into operational plans. Determination, monitoring, and review of program scope, costs, and schedule, program resources, inter-dependencies, and program risk. | 7 |

| Project management | The management of projects, typically (but not exclusively) involving the development and implementation of business processes to meet identified business needs, acquiring and utilizing the necessary resources and skills, within agreed parameters of cost, timescales, and quality. | 7 |

| Systems development management | The management of resources in order to plan, estimate, and carry out programs of solution development work to time, budget, and quality targets and in accordance with appropriate standards, methods, and procedures (including secure software development). The facilitation of improvements by changing approaches and working practices, typically using recognized models, recommended practices, standards, and methodologies. The provision of advice, assistance, and leadership in improving the quality of software development, by focusing on process definition, management, repeatability, and measurement. | 7 |

| Relationship management | The identification, analysis, management, and monitoring of relationships with and between stakeholders. (Stakeholders are individuals, groups, or organizations who may affect, be affected by, or perceive themselves to be affected by decisions, activities, and outcomes related to products, services, or changes to products and services). The clarification of mutual needs and commitments through consultation and consideration of impacts. For example, the coordination of all promotional activities to one or more clients to achieve satisfaction for the client and an acceptable return for the supplier; assistance to the client to ensure that maximum benefit is gained from products and services supplied. | 7 |

| Sourcing | The provision of policy, internal standards, and advice on the procurement or commissioning of externally supplied and internally developed products and services. The provision of commercial governance, conformance to legislation, and assurance of information security. The implementation of compliant procurement processes, taking full account of the issues and imperatives of both the commissioning and supplier sides. The identification and management of suppliers to ensure successful delivery of products and services required by the business. | 7 |

| Quality management | The application of techniques for monitoring and improvement of quality to any aspect of a function or process. The achievement of, and maintenance of compliance to, national and international standards, as appropriate, and to internal policies, including those relating to sustainability and security. | 7 |

| Service level management | The planning, implementation, control, review, and audit of service provision, to meet customer business requirements. This includes negotiation, implementation, and monitoring of service level agreements, and the ongoing management of operational facilities to provide the agreed levels of service, seeking continually and proactively to improve service delivery and sustainability targets. | 7 |

| Information assurance | The protection of integrity, availability, authenticity, non-repudiation, and confidentiality of information and data in storage and in transit. The management of risk in a pragmatic and cost-effective manner to ensure stakeholder confidence. | 6-7 |

| Information security | The selection, design, justification, implementation, and operation of controls and management strategies to maintain the security, confidentiality, integrity, availability, accountability, and relevant compliance of information systems with legislation, regulation, and relevant standards. | 6-7 |

| Business risk management | The planning and implementation of organization-wide processes and procedures for the management of risk to the success or integrity of the business, especially those arising from the use of information technology, reduction or non-availability of energy supply, or inappropriate disposal of materials, hardware, or data. | 7 |

10.2 European Competency Framework

The European Union's European e-Competence Framework (e-CF) has 40 competences and is used by a large number of companies, qualification providers, and others in public and private sectors across the EU. It uses five levels of competence proficiency (e-1 to e-5). No competence is subject to all five levels.

The e-CF is published and legally owned by CEN, the European Committee for Standardization, and its National Member Bodies (www.cen.eu). Its creation and maintenance has been co-financed and politically supported by the European Commission, in particular, DG (Directorate General) Enterprise and Industry, with contributions from the EU ICT multi-stakeholder community, to support competitiveness, innovation, and job creation in European industry. The Commission works on a number of initiatives to boost ICT skills in the workforce. Version 1.0 to 3.0 were published as CEN Workshop Agreements (CWA). The e-CF 3.0 CWA 16234-1 was published as an official European Norm (EN), EN 16234-1. For complete information, see http://www.ecompetences.eu.

| e-CF Dimension 2 | e-CF Dimension 3 |

|---|---|

| A.1. IS and business Strategy Alignment (PLAN) Anticipates long-term business requirements, and influences the improvement of organizational process efficiency and effectiveness. Determines the IS model and the enterprise architecture in line with the organization's policy and ensures a secure environment. Makes strategic IS policy decisions for the enterprise, including sourcing strategies. | Level 4-5 |

| A.3. Business Plan Development (PLAN) Addresses the design and structure of a business or product plan including the identification of alternative approaches as well as return on investment propositions. Considers the possible and applicable sourcing models. Presents cost-benefit analysis and reasoned arguments in support of the selected strategy. Ensures compliance with business and technology strategies. Communicates and sells business plan to relevant stakeholders and addresses political, financial, and organizational interests. | Level 3-5 |

| A.4. Product/Service Planning (PLAN) Analyzes and defines current and target status. Estimates cost effectiveness, points of risk, opportunities, strengths, and weaknesses, with a critical approach. Creates structured plans; establishes time scales and milestones, ensuring optimization of activities and resources. Manages change requests. Defines delivery quantity and provides an overview of additional documentation requirements. Specifies correct handling of products, including legal issues, in accordance with current regulations. | Level 2-4 |

| D.3. Education and Training Provision (ENABLE) Defines and implements ICT training policy to address organizational skill needs and gaps. Structures, organizes, and schedules training programs and evaluates training quality through a feedback process and implements continuous improvement. Adapts training plans to address changing demand. | Level 2-3 |

| E.1. Forecast Development (MANAGE) Interprets market needs and evaluates market acceptance of products or services. Assesses the organization's potential to meet future production and quality requirements. Applies relevant metrics to enable accurate decision making in support of production, marketing, sales, and distribution functions. | Level 3-4 |

| E.2. Project and Portfolio Management (MANAGE) Implements plans for a program of change. Plans and directs a single or portfolio of ICT projects to ensure coordination and management of interdependencies. Orchestrates projects to develop or implement new, internal or externally defined processes to meet identified business needs. Defines activities, responsibilities, critical milestones, resources, skills needs, interfaces, and budget, optimizes costs and time utilization, minimizes waste, and strives for high quality. Develops contingency plans to address potential implementation issues. Delivers project on time, on budget and in accordance with original requirements. Creates and maintains documents to facilitate monitoring of project progress. | Level 2-5 |

| E.7. Business Change Management (MANAGE) Assesses the implications of new digital solutions. Defines the requirements and quantifies the business benefits. Manages the deployment of change taking into account structural and cultural issues. Maintains business and process continuity throughout change, monitoring the impact, taking any required remedial action and refining approach. | Level 3-5 |

| E.9. IS Governance (MANAGE) Defines, deploys, and controls the management of information systems in line with business imperatives. Takes into account all internal and external parameters such as legislation and industry standard compliance to influence risk management and resource deployment to achieve balanced business benefit. | Level 4-5 |

10.3 i Competency Dictionary

The Information Technology Promotion Agency (IPA) of Japan has developed the i Competency Dictionary (iCD), translated it into English, and describes it at https://www.ipa.go.jp/english/humandev/icd.html. It is an extensive skills and tasks database, used in Japan and southeast Asian countries. It establishes a taxonomy of tasks and the skills required to perform the tasks. The IPA is also responsible for the Information Technology Engineers Examination (ITEE), which has grown into one of the largest scale national examinations in Japan, with approximately 600,000 applicants each year.

The iCD consists of a Task Dictionary and a Skill Dictionary. Skills for a specific task are identified via a "Task x Skill" table. (See Appendix A for the task layer and skill layer structures.) EITBOK activities in each chapter require several tasks in the Task Dictionary.

The table below shows a sample task from iCD Task Dictionary Layer 2 (with Layer 1 in parentheses) that correspond to activities in this chapter. It also shows the Layer 2 (Skill Classification), Layer 3 (Skill Item), and Layer 4 (knowledge item from the IPA Body of Knowledge) prerequisite skills associated with the sample task, as identified by the Task x Skill Table of the iCD Skill Dictionary. The complete iCD Task Dictionary (Layer 1-4) and Skill Dictionary (Layer 1-4) can be obtained by returning the request form provided at http://www.ipa.go.jp/english/humandev/icd.html.

| Task Dictionary | Skill Dictionary | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Task Layer 1 (Task Layer 2) | Skill Classification | Skill Item | Associated Knowledge Items |

| Formulation of basic policies (EIT strategy formulation and execution promotion) |

System strategy planning methods | Computerization strategy methods |

|

11 Key Roles

Both SFIA and the e-CF have described profiles (similar to roles) for providing examples of skill sets (skill combinations) for various roles. The iCD has described tasks performed in EIT and associated those with skills in the IPA database.

These roles are common to ITSM:

- Availability Manager

- Business Relationship Manager

- Capacity Manager

- Enterprise Architect

- Financial Manager

- Risk Manager

- Service Catalog Manager

- Service Portfolio Manager

- Service Continuity Manager

- Supplier Manager

Other roles can include:

- Architect

- Board of directors

- Business management team

- Business partners

- C-level officers

- Governance body

- Regulatory authority

- Stockholder

- Vendor

12 Standards

Commonly used formal risk standards include:

- ISO 31000 2009—Risk Management Principles and Guidelines

- ISO/IEC 31010:2009—Risk Management—Risk Assessment Techniques

- ISO/IEC 16085:2006, System and Software Engineering—Lifecycle Management—Risk Management

- ISO/IEC 38500:2015, Information technology—Governance of EIT for the organization

13 References

[1] http://searchcio.techtarget.com/definition/IT-strategic-plan-information-technology-strategic-plan, accessed 1/19/2017.

[2] R. S. Kaplan and D. P. Norton, Strategy Maps: Converting Intangible Assets into Tangible Outcomes (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2004).

[3] www.hoshinkanripro.com.

[4] Business Motivation Model (BMM), www.omg.org/spec/BMM.

[5] OMG Business Architecture Special Interest Group, http://bawg.omg.org, and Business Architecture Institute, www.businessarchitectureinstitute.org.

[6] A Guide to the Business Architecture Body of Knowledge (BIZBOK® Guide), Release 4.1, Glossary, Business Architecture Guild, www.businessarchitectureguild.org (download at http://www.businessarchitectureguild.org/resource/resmgr/BIZBOK_5_5publicDocs/BIZBOK_v5.5_Glossary_FINAL.pdf.)

[7] A Common Perspective on Enterprise Architecture, The Federation of Enterprise Architecture Professional Organizations (FEAPO), 2013, www.feapo.org.

[8] A Guide to the Business Architecture Body of Knowledge (BIZBOK® Guide), Release 4.1, Section 1, Introduction, Business Architecture Guild, www.businessarchitectureguild.org.

[9] For change management guidance—Project Management Body of Knowledge, Chapter 4 Version 5 December 31, 2012.

[10] IT Governance: How Top Performers Manage IT Decision Rights for Superior Results, Peter Weill and Jeanne Ross, Harvard Business School Press, 2004.

[11] Porter, M.E. (2008). The Five Competitive Forces That Shape Strategy, Harvard Business Review, January 2008, pp. 79–93.

[12] Lapkin, Anne, & Young, Colleen M. (2011). The Management Nexus: Closing the Gap Between Strategy and Execution, Gartner.

14 Additional Useful Sources

- Enterprise Architecture as Strategy: Creating a Foundation for Business Execution, Peter Weill and Jeanne Ross, Harvard Business School Press, 2006.

- ITGC—EIT Global Controls—Global Technology Audit Guide (GTAG), Institute of Internal Auditors.

- IEEE Code of Ethics and ACM Code of Ethics and Professional Conduct as examples.

- Control Objectives for Information and related Technology (COBIT).

- DAMA-DMBOK Guide to the Data Management Body of Knowledge (DAMA-DMBOK), Chapter 4 Data Governance.

- EIT Risk Management guidance—ISACA.

- The SEI Capability Maturity Model Integration (CMMI) for software development and for EIT services.

- Project Management Institute, Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK) guide.

- R. Kaplan and D. Norton, Using the Balanced Scorecard as a Strategic Management System, July 10, 2015, https://hbr.org/2007/07/using-the-balanced-scorecard-as-a-strategic-management-system.

- COSO2004—Enterprise Risk Management—Integrated Framework

- OCEG "Red Book" 2.0: 2009—a Governance, Risk, and Compliance Capability Model

- A Risk Management Standard—IRM/Alarm/AIRMIC 2002—developed in 2002 by the UK's 3 main risk organizations