What Makes Up a Life Cycle?

Contents

1 What is a Life Cycle?

In Part 1, we discussed the on-going critical functions that enable enterprise information technology (EIT) to carry out its mission of supplying high-quality, reliable information, and communication series. Part 2, discusses the life-cycle perspective, from concept — expanded into a set of requirements — to transition, then deployment, and finally retirement.

The term life cycle is used to refer to the stages (or just the duration) of things that have a beginning and an end, changing form (maturing, usually) along the way. Appliances have “useful” lives, a term that describes the core part of the appliance’s lifecycle, for example. Life cycles are not the same as methodologies (collections of methods). Many different options for methods can be used to carry out the activities in the lifecycle, e.g., to design and build a product.

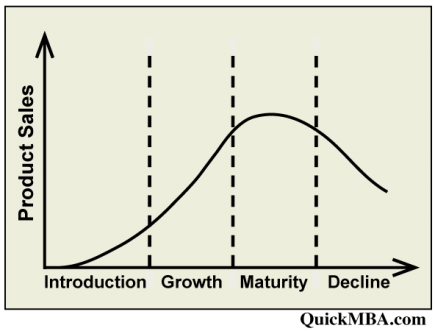

Some views of a product life cycle include the marketing perspective of a life cycle, which focuses on sales.

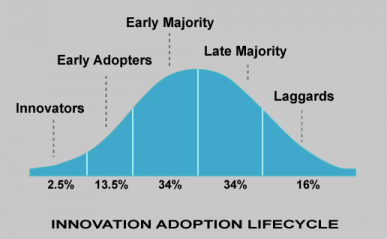

There is also an innovation adoption lifecycle that describes who adopts new technologies, originally described by Everett Rogers in his Diffusion of Innovations theory, and later popularized by Geoffrey Moore’s book Crossing the Chasm (3rd edition, HarperCollins, 2014).

1.1 Product Life Cycles

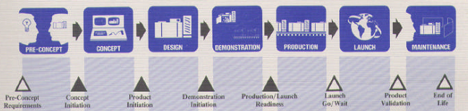

Another view is that of the producer, or the product manager, responsible for managing the lifecycle of the product, from design through production and maintenance to retirement (including simply withdrawal of support). The whole product lifecycle for an appliance looks like this (note the milestones in the bottom row and the inclusion of “end of life” as the last milestone).

The sequence is the same for software, except that “production” includes building and testing the software , and then “manufacturing” the media in which it will be delivered (CD, tape, tar file, etc.). Unfortunately, most diagrams of the software life cycle are usually abbreviated, showing just the parts that developers focus on. Given that there are still legacy systems running Cobol, it’s easy to see why retirement gets ignored! However, software product companies do have to consider sunsetting (retiring) their products, so that they don’t have to support them forever, as newer versions are sold.

1.2 Project Life Cycles

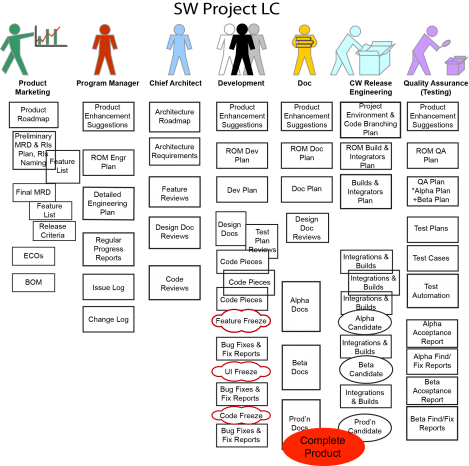

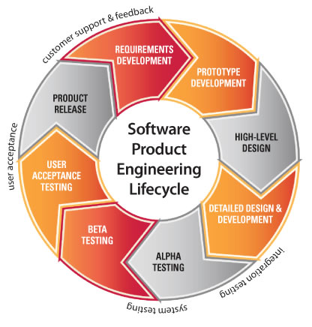

The software world has often conflated the ideas of product lifecycle with project lifecycle. A project lifecycle has a beginning, when the project is authorized, for example, and an end. However, many projects may be involved in creating and refining a software product. There might be a project to define the requirements for a project by developing a working prototype, or a demo version. Once that’s approved, there is a project to develop and deliver the first version of the product. (Often, with agile methodologies, we see that each iteration has its own project plan and follows the same sequence of activities in each iteration. Thus, each iteration is a sub-project that has its beginning and end, ergo, a life.) Here is an example of the activities in a project lifecycle in a software product company:

Reducing the level of detail given above, we can arrive at the typical circular depiction of a project lifecycle, although it is often mistakenly called a product lifecycle. Here is the circular diagram

2 Projects and Project Management

Projects are defined as scope (features and constraints), schedule, and resources. Project management is the balancing act of producing the desired scope of requirements, within the planned schedule and within the budgeted resources. Management of the key resources — the people — is the pivotal management skill, because the people are the major costs and the primary determiners of schedule.

There are usually too many unknowns to be able to predict exactly what it will take to produce the required scope, so project management depends on various approaches and mechanisms to estimate cost and duration, both with high-level estimates up front and with increasingly precise estimates as the project progresses.

The Software Extension to the Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK), jointly produced by IEEE and PMI, explains how these tools are used in both predictive and waterfall development. It can also be used for projects that involve hardware. Another good resource for projects building large systems, or systems of systems, is the Guide to the Systems Engineering BOK (SEBOK), which is a wiki produced jointly by IEEE and INCOSE.

The project approach is used both for new development (greenfield) and for the production of subsequent system revisions. There are many reasons for using the project approach (projectizing) for system revisions rather than handling changes as a stream of independent user requests. One important one is that bundling change requests together makes it more likely that one change won’t “break” the system in the production. Another is that it enables EIT to better contain its costs. For years, EIT has had to deal with complaints that 80% of its budget goes to “maintenance” while requests for new services pile up and take forever. By surveying all change requests, it is easier to prioritize them using portfolio management, and bundle high-priority changes into projects, so that resources are applied where most appreciated.

3 EIT System Development Life Cycles

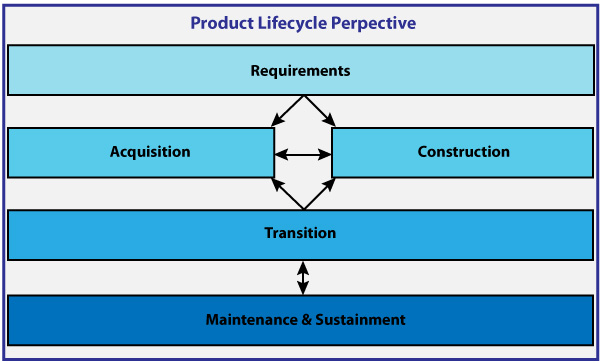

An information system or service is a product that satisfies a want or need. The product life cycle is the course of a product’s design, development, use, and retirement over the system’s lifetime.

In the EITBOK, we have adopted a fairly traditional product life cycle with six commonly accepted phases. Despite the fact that these phases (or stages) appear to occur in a clear sequence from one to another, in reality, for any given solution/system development, several phases can be going on simultaneously. How the phases are executed depends on the solution type, size, and complexity, as well as the specific development methodologies that the EIT organization has adopted.

“Agile” methodologies were a reaction to what has been termed waterfall development. Waterfall was seen in situations where a third-party developer, whether for the government or for an enterprise, needed to ensure customer acceptance at prescribed milestones. The easiest way they saw to do this was to have major milestone reviews at which progress to date was approved. As major milestones, the end of the logical phases in the development life cycle were selected: requirements, design, test, and integration into a larger system when necessary. Unfortunately, these had the unintended consequence of holding up pieces of the product while others were being worked on. On the other hand, in software product companies, Product Management, Development, and Testing worked closely throughout the development of the product, so approvals frequently occurred at the feature level for requirements and design. They also used continuous integration, so it was obvious early on when features didn’t play together well.

3.1 Requirements Analysis and Design

The analysis and design phase involves gathering information about what the organization needs, what the solution must accomplish, what data is needed, and what business rules drive the process. Systems analysis attempts to answer the question “What must the information system do to solve the problem?" From those requirements, the team creates a detailed conceptual design of what the solution must do, how it interacts with users and other EIT resources, and how to determine whether it is successful.

3.2 Acquisition

Acquisition is the process of obtaining a system, product, or service and ensuring its successful implementation, whether the supplies or services already exist or must be created, developed, demonstrated, and evaluated. Acquisition also includes ensuring that proper mechanisms are in place to monitor the supplier’s/vendor’s performance in providing support and fulfilling other contractual obligations.

3.3 Solution Construction

Construction is the system development phase that involves actually creating all of the various system components called for in the conceptual design so they work together as expected. It may include the need to revisit designs that proved unworkable, or even to re-examine requirements. For this reason, many agilest developers prefer to say that the finished system is the final documentation of the requirements. However, those who work on subsequent revisions of the production system might bemoan the lack of explanation of the rationale for design.

3.4 Solution Transition

Transition consists of a set of processes and activities that release new solutions into an EIT environment, replace or update existing solutions, remove a solution or component from service, or move EIT components from one location to another. Examples of transition include the installation of a new software application, migration of an existing hardware infrastructure into a new location, a refresh of key business applications with new software, or decommissioning a datacenter, hardware, or network devices.

3.5 Maintenance

Maintenance (or support) of an EIT system involves the set of activities performed to ensure that the system remains operational. This includes actions necessary to prevent the deterioration and failure of a system due to defects, obsolescence, or environmental conditions.

Traditional definitions of maintenance include the evolution of a system via the application of enhancements. However, system evolution is actually a type of new development, sometimes called brownfield (to distinguish it from greenfield development). Brownfield development is often a lot harder than greenfield, because it adds many constraints set by the existing system’s architecture and other factors.