Strategy and Governance

Note: This wiki is a work in progress, and may contain missing content, errors, or duplication.

Contents

1 Introduction

Enterprise information technology (EIT) strategic planning defines the goals of the EIT organization and communicates those goals --and how they support the enterprise's goals, while EIT governance assesses their impact on the organization, and drives change to achieve those goals. Taking into account various perspectives (financial, historical, environmental, future projections), a strategic plan is a framework for action and change, both vertically and horizontally, across the EIT organization. EIT governance is based on the EIT and enterprise strategic plans and acts as a control framework to achieve and sustain strategic goals and objectives. Thus, EIT governance is completely interdependent with the EIT strategy.

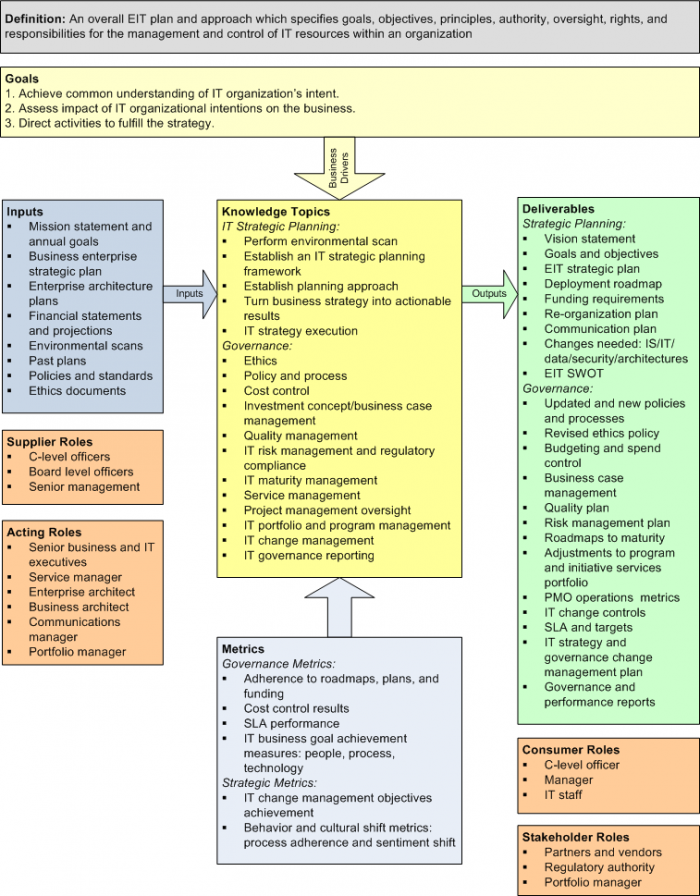

The nature of the enterprise's and EIT's goals and objectives depends on the type, status, and size of the enterprise. For example, the main goal of EIT development for a trading company might be to support the rate of turnover of the warehouse, but for a consulting company the important goal might be assuring full utilization of all consultants on client engagements.</p>This chapter provides an overview of EIT strategic planning and governance including the approaches to create an EIT strategic plan based on enterprise strategy, and the role of the EIT architecture. The strategic planning and governance context diagram is shown in Figure 1.

2 Goals and Principles

- EIT strategy — To achieve a common understanding of EIT and enterprise intent:

- Recognize that enterprise strategy drives EIT strategy.

- Understand your purpose for creating an EIT strategy.

- Understand current EIT operations.

- Plan for working on the things that matter to enterprise.

- Take a multi-year perspective, and revisit the plan on a periodic basis for confirmation or changes.

- Enable reliable, nimble, and efficient response to strategic objectives.

- Sustain EIT capability.

- EIT governance — The goal of governance is to direct activities in a way that fulfills the EIT strategy. These are critical activities required to achieve this goal:

- Plan for flexibility and change in governance structure, accountability, and priorities.

- Measure progress and performance against the strategic roadmap as well as on a project and operations basis.

- Enable change, even to the plan itself, as required.

- Advise and align other EIT discipline strategic plans into an overall framework for delivery.

- Foster communications and understanding between EIT and enterprise.

- Set expectations within a code of ethics framework.

- Foster a continuous learning organization.

- Look ahead for continuity planning as part of risk management planning.

3 Context Diagram

Figure 1. Strategy and Governance Context Diagram

4 Description

The inputs to strategy and governance include various enterprise planning and strategy inputs, financials (budgets, plans, and performance), as well as enterprise architecture and enterprise governance artifacts including policies.

The roles involved in supplying input to and drafting EIT strategy and governance include C-level executives, senior management, and certain specialists such as communications personnel and architects.

While strategic planning occurs at different organization levels, and horizontally as well, it must be coordinated so that there is a hierarchy of strategic plans for each unit of the enterprise that defines how each unit supports the next higher level. Although EIT strategy is developed by senior management, it needs to be supported by EIT standards, frameworks, and guides to facilitate EIT self-governance activities.

Deliverables from the strategic planning process include the strategic plan, the communication plan, and the socialization plan. They inform a governance framework necessary to deploy those plans in EIT. These deliverables are consumed by C-level executives and business and EIT management and staff.

4.1 EIT Strategic Planning

4.1.1 Introduction: EIT Strategy is a Business Strategy

EIT is a business unit within the enterprise. The enterprise's business strategy document is the most significant single input to the EIT strategy document. The business strategy frames the scope and expectations for the EIT strategy. Any supply chain, outsourcing, onboarding, or other EIT practice, should be driven out of this strategy. For example, if the business chooses to add vendor relationships, the focus would be on a value stream called an onboard supplier, and capabilities that would include partner management, asset management, agreement management, and related capabilities that are supported by associated EIT capabilities in these areas.

The resulting activities could involve consolidating and improving automation around this value stream and capabilities, as well as numerous other non-technical activities that do not involve systems and technology. Specific topics may include best practices on:

- Outsourcing of systems, process, maintenance, technical risk management and transition approaches, cloud contracting advice, mobile strategies, data and information management and integration strategies, SLA framework strategies, logistical and business cultural constraints, and resource optimization options.

- EIT strategy is a component of an enterprise strategy when considering activities that include designing, building, and managing information and information technology for business change. [1]

4.1.2 Perform Environmental Scan

There are multiple ways to leverage the concepts portrayed in Figure 1. However, the process begins with strategy mapping.

A current assessment of EIT systems, capabilities, and resources is necessary to complete the full 360 degree scan.

EIT maturity assessment results are input to strategy mapping and desired outcomes. See EIT Maturity Management for an overview of the assessment process.

Strategy mapping has existed in one form or another for some time. Sample strategy mapping approaches that apply to enterprise and EIT strategies are listed below:

- Strength/weakness/opportunity/threat (SWOT) analysis

- SWOT surfaces internal and external perspectives that should be capitalized on or otherwise addressed. SWOT findings are one input to strategy formulation providing possible focal points in strategy development.

- The Norton Kaplan Strategy Map [2] links actions to value creation along four dimensions: financial, customer, internal (employees), and learning and growth. The strategy map offers a complete, in-context perspective on the strategy.

- Hoshin Kanri [3] provides similar cross-mapping concepts include tying mission, goals, and objectives with action items, and key performance indicators (KPIs).

- The business motivation model (BMM) [4] provides a mapping between the ends to be achieved (i.e., goals and objectives) and the means (i.e., strategies and tactics) needed to achieve those ends.

Generally only one approach is selected for a strategy map. Regardless of the approach taken, the end result of any strategic EIT planning process is a clear set of measurable objectives, priorities, and action items that management can act on to deliver change leading to improved EIT performance.

4.1.3 Establish an EIT Strategic Planning Framework

The strategic planning context diagram shown in Figure 1 provides a good focal point for strategic planning from a business, process, and EIT perspective. In practice, EIT strategy formulation incorporates business strategy as a fundamental driver.

EIT strategy is deployed by leveraging the best architecture, design practices, and technologies. The tension between delivering systems that meet business objectives, particularly from a tactical perspective, must deliver solutions in a delicate balance between forward-looking tools and techniques, current practices, and pressures to implement quickly.

4.1.4 EIT Strategy Formulation

Drafting an EIT strategy requires alignment with enterprise and business strategies, measured adherence and compliance to EIT best practices, and governance. While enterprise and business strategies come from business, adherence to best practices falls within the EIT domain. Of course, best practices continue to evolve and differ from organization to organization and even project to project. Therefore, EIT faces the challenge of satisfying strategic business objectives through the application of evolving and situational best practices.

Best practice conformance can be difficult when EIT owns numerous systems that were designed and developed in a prior era. Sometimes we call these legacy or heritage systems, and, in most cases, these older systems come with challenges. These systems were typically developed using older technologies and their architecture often does not conform to modern design principles (e.g., SOA) or to the current business needs. In addition, changing business architecture and rules can, over time, lead to data- and information-quality issues. Lack of business alignment and data-quality issues are some of the more difficult and time-consuming issues to address.

EIT organizations typically address technical debt through legacy modernization (upgrade or replacement), but often do not tie these projects to strategic business objectives. Additionally, the costs are often high and the business benefits for continuing to deliver the same functionality as before upon completion of the project can be a hard sell to the business.

The following six-stage framework for EIT strategic planning ensures that the business strategy is integrated into the planning process and that EIT strategy is not driven solely by technological upgrades:

- Craft the EIT strategy and plan to support well-articulated enterprise and business objectives.

- Leverage EA to feed the strategy. Vet various perspectives.

- Highlight EIT focal points for each objective.

- Establish KPIs for each strategic enterprise objective and related action item.

- Establish a plan timeline roadmap including a review plan.

- Establish or leverage EIT governance to ensure that business strategy is realized.

Each of these stages presents a unique challenge and occasionally can be in conflict with another stage. For example, adherence to best EIT architecture practices is difficult when architecturally inelegant legacy systems must be updated to accommodate the current business strategy, or when time-to-implement constraints override preferred plans. When a conflict occurs, the organization begins to build technical debt. Technical debt is defined as “the negative effects of applying ill-advised or problematic changes or additions to software systems and their data, negatively impacting the delivery of future business value.” [5]

As depicted in the context diagram in Figure 1, the steps in the planning process should work for most organizations as they embark upon their business and EIT planning efforts, keeping in mind that the framework provides a guide into what should specifically be addressed at each stage of the planning process. Finally, much of what is considered as strategic planning within EIT is just a portion of the broader context for business planning. Therefore, planning for EIT and business scenarios that are essentially the same scenario, such as outsourcing a capability or managing suppliers, should take an integrated, holistic, and enterprise view of the planning process.

4.1.5 Establish Planning Approach

A defined EIT strategy provides the roadmap needed for getting from where the enterprise is at present to where it needs to be. The strategy identifies how the enterprise needs to change. EIT must determine effective ways to take the enterprise strategy and transform it into EIT strategic change.

Strategic change employs a wide array of disciplines and techniques to enable change on a large scale and on an incremental basis. These techniques are often discussed in the context of types of focuses, such as: [6]

- Governance

- Information/data

- Solution

- Technology

- Security

Each focus has constraints that must be understood and reflected explicitly in the strategy. These typically include time, quality, and cost. The focus may also include organizational scope such as Western Hemisphere operations only, or a timeframe such as a 2-year horizon, as well as constraints from the environmental scan such as regulatory requirements for the industry. An EIT strategy also acknowledges existing EIT constraints through enterprise architecture (EA), human resources, legacy systems, staff capability, and capacity to deliver.

The strategic planning team takes risk into account within the plan. They recognize the risk appetite of the organization as a potential constraint in the plan. They also suggest risk responses that require vetting and approval as part of overall strategy adoption.

4.1.6 Role of Architecture in Strategy Planning

Enterprise architecture (EA) informs the EIT strategic plan in a number of ways. EA supplies “a blueprint of the enterprise that provides a common understanding of the organization and is used to align strategic objectives and tactical demands.” [7]

Standard methods include strategy maps, capability maps, information maps, value maps, and organization maps.

Some other artifacts include operating models, product maps, stakeholder maps, process models, dynamic rules-based routing maps, data models, network models, systems models, vitality and renewal plans, and a wide range of hybrid blueprints and models that have specialty uses based on the challenge at hand.

Blueprints and models provide valuable input to the EIT strategic plan. Typically, few artifacts exist when initiating a strategic planning effort and they must be developed together with business input. The EIT strategy document then becomes an extrapolation from the enterprise strategy with an EIT lens.

4.1.6.1 Blueprints and Models — Business and EIT

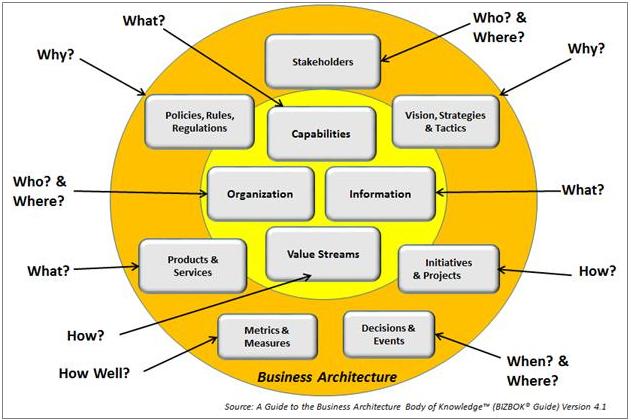

Blueprints and models require consistent, standardized components. These components draw from the abstract representations of the business shown in Figure 2. In the figure, the center circle represents concepts and includes capability, value, organization, and information. These concepts are considered core, because they are very stable business and EIT perspectives that remain relatively constant. Changes occur as required to accommodate business and EIT as they evolve. EIT inherits some of these blueprints from the business and transforms them into aligned, EIT-focused forms.

The yellow circle in the figure shows influencing perspectives. For example, strategies continue to evolve in real time while new business and EIT products and services are introduced routinely. These examples show how the outer circle of business abstractions are more dynamic than the stable core. Collectively, when mapped and presented appropriately, the core and extended views provide a complete and holistic planning view.

Figure 2. Business Architecture Ecosystem [8]

Sophisticated blueprint mappings can emerge from the collection of components shown in Figure 2, which represents the business ecosystem. Even simple concepts, like value stream or capability cross-mapping, serve as a basis for business-driven roadmaps and investment planning. Collectively, all of these perspectives answer important questions such as why take action, what is impacted, or how to accomplish a particular task.

4.1.7 Turn Business Strategy into Actionable Results

4.1.7.1 Using Blueprints and Models

The reason for developing the various blueprints and models is to use them in some way to achieve strategic and tactical needs. Strategy drives changes that can be collectively represented by abstractions depicted in Figure 2. When management has the ability to view the impact of change using these abstractions, everyone from the executives and planning teams to the deployment teams can have a shared perspective of the context and scope of these changes.

For example, consider the goal to provide more customer and transactional transparency throughout the product sales cycle; where “transparency” across the sales cycle means visibility into transaction history and sales potential. Business architects would determine that this strategy targets the acquire product value stream and account file management, customer management, and account routing capabilities. Other enterprise and solution architects would then look at the goal from their delivery perspectives. These perspectives are likely implemented today using a cross-section of technologies and processes, some of which are well understood and adaptive, while others are not. Together with EA, the EIT strategy provides a framework for assessing current state implementations, crafting target-state solutions, and establishing a transition strategy for moving from current to target state solutions.

There are many strategic planning approaches. Regardless of the approach selected, turning strategies into actionable results requires identifying the EIT delivery impacts on the current state and current future state plans.

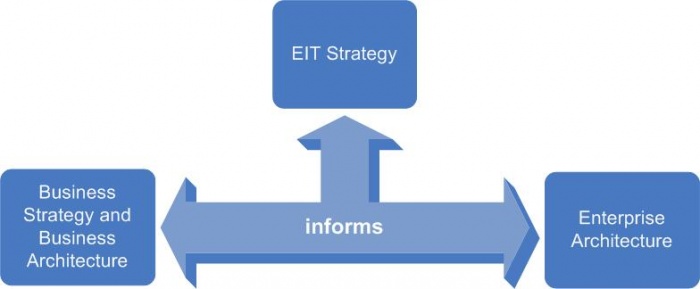

Figure 3. Turning Strategy into Actionable Results via Enterprise Architecture

Figure 3 represents the ability to leverage perspectives to identify specific areas of EIT that require initiative investment. In turn, these investments result in projects that incorporate business and EIT transformations.

- Business strategy represents all motivational factors including policy, regulation, goals and objectives, product and stakeholder considerations, and the resulting action items required to achieve various goals and objectives.

- EIT strategy represents the EIT perspective of the enterprise business strategy and includes capability, capacity, ROI, information, organizations, responsibilities, funding plan, stakeholders, initiatives, products, and decisions.

- Enterprise architecture identifies actionable items as inputs to design concepts, EIT business priorities, business-driven roadmaps, fundable initiatives, and business-driven EIT architecture transformation.

4.1.7.2 Using Enterprise Architecture to Interpret Business Strategy [9]

EA is both an input to the strategy by supplying methods and as-is architectures, and a follow-on activity that interprets, performs gap analysis, and supports execution the strategic plan and adjusts the to-be architectures to new or changed direction from the plan.

A brilliant business design can be too costly and take too long to satisfy executive demands, or can be technologically infeasible. This is where enterprise architecture can help ensure that selected business designs and innovation options are not only desirable, but cost effective and implementable.

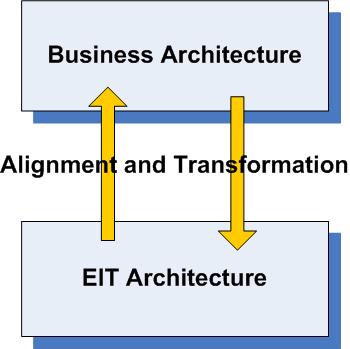

We stated earlier that EA includes business, solution, information, and technology architectures. Business architecture has a direct relationship to and reciprocal impact on the remaining aspects of EA, particularly solution and information architectures. For example, information architecture leverages the information aspects of business architecture to craft a wide range of technology options for maximizing accessibility and usage to a various information categories. These range from “big data” to more traditional relational database architectures. Information architecture establishes the critical underpinnings for business automation solutions.

The solution architecture is the implementation perspective of the business architecture and includes business design concepts such as case management and process management. Business capabilities drive the evolution of applications and service-oriented architecture (SOA) service deployments. Value streams provide the framework for service orchestration, business design options, and stakeholder interface requirements.

The technology architecture plays two important roles. First, it enables the delivery of business solutions as articulated through the blueprints and models. Second, it ensures that the required degree of technological innovation is in place to maximize business solutions while ensuring stability, security, and business continuity.

Figure 4. Business Architecture and Continuous Business/EIT Alignment

The two-way relationship between business architecture and solution, information, and technology architecture is depicted in Figure 4. Continuous business/EIT alignment reflects the value of maintaining these interdependent relationships across business and EIT. A change in either of these aligned layers should be transparent, duly assessed to determine reciprocal impacts, clearly linked to a specific business objective, and addressed through a funded initiative.

When business needs are mapped appropriately to current and future EIT plans, it ensures that business objectives are known, quantified, clearly articulated, and linked to business value. Any EIT investment must also demonstrate a link back to business value. For example, an application change may require significant funding. Architects should be able to trace the planned application process changes back to the business capabilities, value streams, and information that the change implements, and back to business objectives and link the change to value. A network planning team, for example, should be able to trace the usability of that network up the chain, through the solution architecture, and directly into the business architecture. In this way, all EIT activities can be tied back to business impacts and business strategy.

Business architecture not only helps identify change impacts and investment focal points derived from a given business strategy, but also provides a basis for business design and innovation analysis.

Consolidated platforms (CP) are emerging as multi-vendor pre-packaged solutions that can efficiently use resources in operations and release management activities with the providers in an oversight role; however, evaluating the detailed solution for suitability and viable exit planning becomes more complex. CP can be seen as a mid-way solution between complete solution insourcing and complete outsourcing.

4.1.8 EIT Strategy Execution

Poor strategy execution is the most significant management challenge facing public and private organizations in the 21st century according to Gartner (Lapkin & Young, 2011). [10]

Figure 5. Change Initiative Flow Chart ***need images

All strategies must be grounded with the following rigorous practices:

- Outline the means for achieving desired outcomes:

- Specify timeframes and business scope that reflect needs and priorities.

- Link all EIT strategies to business goals and objectives.

- Create and support a means to generate and capture ideas for innovation and change, and their evaluation.

- Support change-management processes with top-down and bottom-up validation.

- Provide properly scaled strategies for business problems.

- Acknowledge and propose change within known constraints and risks including staffing capability and EA plans.

- Refer to existing funding and planning engagement processes to move the strategy into portfolios and projects.

- Create or refer to control processes in organizations that can give oversight to strategy execution. (Are we doing the right things and are the right things being done well?)

- Ensure that the strategy is a living document and game plan:

- Give targets for strategy achievement and specify reporting to an oversight body.

- Create and live a culture of collaboration between business and EIT through the specification of communications and training plans and change management support.

- Provide adequate and sustained funding.

- Propose active monitoring and adjustment of the strategic plan with renewal cycles.

4.2 Governance

EIT governance establishes a conformance process and authority to make sure the strategic plan is executed. EIT governance accomplishes this by setting into place policies that mandate the instigation of controls in all areas of EIT, including cost controls reporting, project oversight, service management, risk assessment and management, ethical behaviors, and change control. All of these controls fit within a framework of overall organization controls and policies, and are aligned to them.

To ensure full engagement across the business/EIT boundary, business and EIT executive sponsors provide oversight for EIT governance. EIT governance must set expectations at all levels in EIT for compliance using an enterprise and local interaction model for monitoring, guiding, and reporting. The following guidelines can help in this process:

- Understand and work through the people side and the organizational side of proposed change and existing culture impacts. This is critical to the long-term success of strategy implementation and oversight (governance) efforts.

- Establish business/EIT collaboration and a communication governance model.

- Ensure that open communication and collaboration for business-to-business, business-to-EIT, and cross-EIT perspectives.

- Establish collaborative principles, measurements, and escalation procedures as required.

- Ensure that external regulations and laws, market perspectives, and external perspectives are included.

Lines-of-EIT business have their own special concerns that align to overall governance objectives, such as:

- Security — for example, local objectives and measures for blocking threats

- Data — for example, prioritizing key financial data for accuracy in transactions

- Application — for example goals for availability

- Enterprise architecture — for example, overall EIT strategy realization

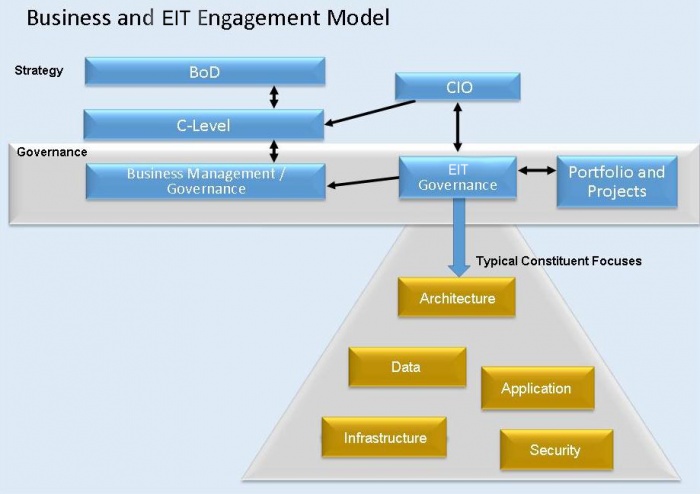

Figure 6. Example of a Business and Governance Engagement Model

Business staff participate at all levels as stewards or subject-matter experts in areas such as legal, marketing, and manufacturing, requiring the EIT services as they set priorities locally that in turn set targets and thresholds for EIT performance.

Enterprise architecture domain experts in application, data/information, infrastructure, and business provide coaching to work teams on an as-needed basis and are the front-line representatives for EIT governance.

4.2.1 Governance Benefits Assessment Realization

Businesses with superior EIT governance record 25 percent higher profits than those with poor governance. [11] This type of positive value assessment for EIT governance is well established and clearly maps to EIT governance objectives of reliable, trusted, responsive, and evolving EIT synced to business plans and needs.

EIT audits are a specialized type of monitoring that challenge the self-reporting on governance metrics by performing direct assessment. [12] Some topics that an audit may cover include:

- Return on investment (ROI)

- Data quality

- Inventory of licenses, hardware in use/owned

- Process performance assurance, rationalization, adherence as required from asserted levels of organization maturity

- Security assurance

- Maturity assessment/reassessment

- Regulatory requirements adherence self-assessment of EIT governance

- Overall assessment of EIT

The resulting reports include gaps found and remediation recommendations.

As a line management and also a virtual organization, the costs to establish and operate EIT governance can be scaled to meet the strategically sensitive areas for the overall organization. Business and EIT share the EIT governance responsibility. Good governance requires exceptional leaders who can communicate across business and EIT subject domains.

The value of EIT assets may not be regularly included on balance sheets. However, EIT governance is asked to participate in a valuation at a time of mergers, acquisitions, and liquidations.

4.2.2 Ethics [13]

Ethical behaviors in an organization are judged relative to their cultural and regulatory framework. In some countries, money paid to gain business advantage is neither unethical nor illegal.

- Ethical assertions should be expressed in EIT, tied to the overall business code of ethics, and signed off by all staff so that violations can be cause for reprimand or dismissal.

- Vendors should be held to similar ethical standards.

- A code of EIT ethics is created, and socialized.

- Lists of employees who have signed off on the code are maintained by EIT governance.

EIT ethical topics include those that may also be illegal, such as:

- Consideration of the social impact of the work at hand — if it will cause harm

- Alignment of business and EIT strategies and policies to an ethical standard

- Incorporation of the ideals of professionalism

- Adherence to applicable regulatory intent

- Protection for whistle blowers

Call out these things specifically:

- Activities that interfere with or corrupt the proper function of computers, applications and systems

- Activities that interfere with digital privacy or intellectual rights of others

- Respect for confidentiality, privacy, permissions, and access rights

- Inappropriate bias (skewing) of analysis and reporting

- Inaction in the face of likely ethics violations

4.2.3 Policy and Process

EIT governance can create numerous policies and processes to establish overall control, or can establish only a few policies that drive action in various delivery areas to create and maintain their own local aligned policies and processes. Determination of the right fit for control should be based on risk assessment by EIT governance and the resulting level of oversight that should be maintained. For example, security policies and processes should typically be set centrally so that all areas of the company are measured on exactly the same basis and changes are uniformly applied. Decentralization and therefore more coordinated information management policies and processes may be acceptable in a business that is more product oriented than service (data) oriented.

Even at the initial phase, an overall EIT governance policy, driven from an enterprise policy, is required to establish its authority.

4.2.4 Cost Control

Cost control is a central activity in EIT governance. EIT products and services are bundled into operations sustainment, major projects, and small changes. Business cases for the work are budgeted, prioritized, and funded. See also Change Initiatives.

The business sets priorities for development and operations. Those priorities must include the factors in the strategic environmental scan. For example, to ensure the rapid expansion of business geography plans, methods and designs may be adopted that diverge from the formal EIT strategies realizing cost savings. The cost control priority can be the important overriding priority that guides the possible easing of EA visions and plans for controlling the overall EIT system evolution, but at the risk of mounting technical debt.

Total cost of ownership (TCO) improvements can be addressed by careful application of strategies, such as:

- Infrastructure allocation/management

- Application rationalization

- Device and data access policies

- Process assessment (identification of wasted effort)

- Application lessons learned

- Feedback loops

- Process improvement/re-engineering

- Licensing re-negotiation

- Various outsourcing initiatives

4.2.5 Investment Concept/Business Case Management

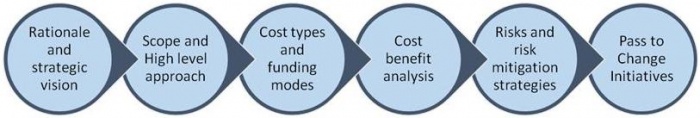

Outside all operations and sustainment work, all activities are proposed through a standard funding process as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7. Steps in Business Case Development

Work is prioritized and moved forward into the realization phase based on the business and EIT strategic plans within the Change Initiatives chapter. The process is monitored for continuing business alignment and need, feasibility factors, stakeholder interest, resourcing opportunities, competitor activity, new EIT tools and approaches, and government requirements in the industry. All of these factors influence the speed at which concepts move through the process or even get dropped entirely from the plan.

Contract management with vendors including outsourcing, licensing, SLA, OLA, cloud computing, and project resourcing is also the responsibility of EIT governance (see also the Acquisition chapter).

4.2.6 Quality [14]

Quality is a key control in EIT governance that is manifested across all policies, processes, and procedures. There are two basic ways of approaching quality. The first is to take a passive approach; in effect to adhere to the idea that quality is “baked in” to the organization through the policies, processes, and procedures, and where quality controls are established as an output measurement much like in manufacturing environments. The second approach is more active, setting out a separate responsibility for quality that establishes responsibility, checks adherence, and advises and reports on quality risk and failures along at many points along work streams.

The adoption of best practices is an indication of a more mature organization requiring active quality-assurance management as part of overall EIT governance. For example, Quality standard ISO 9001 applies when an organization:

- Needs to demonstrate its ability to consistently provide product that meets customer and applicable statutory and regulatory requirements.

- Aims to enhance customer satisfaction through the effective application of the system, including processes for continual improvement of the system and the assurance of conformity to customer and applicable statutory and regulatory requirements.

Monitoring and performing impact analysis of regulatory and changes in industry standards is also a quality assurance activity shared with legal and enterprise architecture.

An organization can address the risk of damage to its reputation and potential fines due to information leakage and misinterpretation by adopting strong data quality-assurance practices within a data-governance program. [15]

The EIT functions described below all have quality dimensions to their activities. See also the Quality chapter.

4.2.7 EIT Risk Management and Regulatory Compliance [16]

EIT policies, standards, and processes all deal with risk to some degree. Policies typically include explicit sections on risk approaches that the organization wants to adopt including EIT security policy, EIT governance policy, EIT financial management policy, data privacy and classification policy, disaster preparedness policy, supply chain management, vendor management, employee ethics, and regulation adherence policy.

Risk management in EIT involves the following activities:

- Risk identification — Relevant EIT risk profiles on systems are specified. Types of risks are financial, reputational, regulatory (projected and current), security, EIT disaster, market innovation speed, and supplier performance.

- Risk evaluation — All identified risks are evaluated for their severity and likelihood.

- Risk response — Response plans are generated for the most severe and likely risks. Generally, the response is either to accept the risk and do nothing because likelihood or organization concern is low, to accept the risk and plan contingencies for the occurrence, or to transfer the risk to a third party via insurance.

4.2.8 EIT Maturity Management [17]

The maturity of EIT functions directly relates to the ability to execute the EIT strategy. Therefore, there is a need to assess maturity as an input to a realistic plan and as a guide to maturing EIT to desired levels. In other words, unless the EIT organization understands its own needs and abilities, it can’t make plans to do more or to improve. The adoption of lessons learned is a key improvement strategy.

Some principles in mounting and actioning maturity assessments are:

- Business and EIT culture and interaction are key elements to capability and performance and cannot be ignored in an evaluation.

- Outputs of the maturity analysis are direct inputs to planning and the strategy plan execution roadmap.

Maturity assessment involves scoring against criteria and a ranking scheme. This assessment is generally organized in ascending steps with strategies on how to move up the maturity scale. Scales are often 1-5 and indicate increasing levels of maturity. Some schemes allow for scoring that includes decimal points (e.g., 2.5).

- Performed: Activities are performed in an ad hoc manner.

- Managed: Activities are performed with managed processes.

- Defined: Activities are defined so the organization can performed them in a uniformed manner.

- Measured: Oversight is given to the performed activities to ensure performance and uniformity.

- Optimized: Continuous improvement processes are in place on the defined and measured processes.

Periodic reassessments are performed to gauge progress against the baseline assessment and prior periods. Adjustments to the efforts to maintain and improve maturity can then be made against possible strategic priority changes, governance initiatives, and roadmap resets.

Maturity assessments on internationally recognized frameworks generally involve external auditors with certification and recertification requirements. Engagement in the maturity assessment and improvement process requires a minimum level of organization self-awareness to the issues and commitment to the improvements necessary. A cultural readiness, resistance, and capability assessment may be built into a maturity assessment.

Bodies of knowledge guides exist as capability and light maturity assessment frameworks many of which are referenced by EITBOK.

Capability Maturity Model Integration (CMMI) [18] is a standard reference model for process improvement with cross-sector applicability with special focuses:

- Product and service development — CMMI for Development (CMMI-DEV)

- Service establishment, management, — CMMI for Services (CMMI-SVC)

- Product and service acquisition — CMMI for Acquisition (CMMI-ACQ)

- Data management — CMMI for Data (CMMI-DMM)

When reviewed and areas prioritized by management, a maturity assessment is an input to the EIT roadmap development for change.

Organizing and communicating for change in order to move up the maturity scale is managed by EIT governance.

EIT governance also provides reality checks on the goals and timing to the desired objectives as materialized through EIT change initiatives. (See also Change Initiatives).

4.2.9 Service Management [19]

Service management in EIT has its own strategic plan encompassing the full system life cycle support from concept to deployment and retirement. It is the EIT function that designs and implements control structures within the EIT governance framework including:

- Service strategy — demand and financial management for service portfolio management; see EIT Strategic Planning

- Service design — Enterprise Architecture, Requirements, and Construction chapters

- Service transition — Transition into Operation chapter

- Service operations — Operations chapter

- Continual service improvement — measurement, monitoring, reporting including monitoring for compliance, financial performance, monitoring customer and employee satisfaction

4.2.10 Project Management Oversight [20]

Project management is an integral part of EIT governance, and a requirement for all change initiatives in EIT including new projects, enhancements, upgrades, and significant operations changes. These include traditional EIT activities as well as supporting activities such as communications and human resources.

EIT governance mandates that project-level controls are initiated and sustained at a level appropriate for the scale of the work that satisfies EIT governance reporting requirements. Required project-level controls include quality, cost, risk, schedule, deliverables, process, and authority.

- All EIT activities require a planning horizon and it is EIT governance that ensures that the adequate resources (including staff, material, and funding) are available to approved activities in a timely manner. In this way, EIT governance at the CIO-level works closely with vendors, project managers, financial management staff, and suppliers to achieve these aims.

- The project management office (PMO) supports a subset of all projects. This formal oversight body is setup to instantiate best repeatable practices in project management and to assist in reporting status. PMO scope is usually limited to those projects holding significant risk to the organization, and significant cost.

4.2.11 EIT Portfolio and Program Management

Reporting and oversight is also applied to aggregates of projects into portfolios and programs. EIT portfolios are a set of scoped applications and systems that are closely interrelated; for example, the accounts payable, accounts receivable, and ledger production in an organization. Programs may span portfolios as multi-phase, multi-year initiatives. Project and portfolio grouping allows for more holistic views on change, impact analysis and synergies, business case development, upgrading, operations problem identification, communication and recovery, vendor and business relationship management, and multi-project oversight.

Portfolio managers work closely with project managers, architects, operations managers, and business users to make sure that the relationships and the understanding between the business and EIT are strong and transparent.

Programs can affect multiple portfolios and often have their own multi-year separate organization structure and board-level interest and oversight. In this way, activities are:

- A new layer of activity that introduces broader change impacting large parts of existing EIT through replacement, incremental improvements, and significant new approaches, such as mobile application, CP, and cloud computing.

- Geared tightly to high business priorities and strategies. Every program is directly linked to achieving specific business (and by inheritance EIT strategy) goals and objectives.

4.2.12 EIT Change Management [21]

The change management function exercises the authority to introduce change into the EIT environment and is the responsibility of both the business and EIT. The governing of change management activities occurs at varying levels of detail depending on the nature of the change. Any change, whether a commissioning of a new system, an application enhancement, a sustainment activity to maintain operations, or corrective action to repair a defect, is approved through governance processes.

- Changes may be at the strategic re-alignment level as plans and architecture responses move to adjust projects and programs that are prioritized or in flight, including the possibility of activity shutdown.

- Changes may be at the operational level where a change control board or change advisory board approves code or systems, or data changes into the production environments and can include planned and unplanned (emergency) changes, projects, and releases.

- Incidents occurring from change handling activities are reported to EIT governance for possible response particularly if additional funding is required for corrective action. Other incident handling occurs at a more local response level.

- Change patterns are monitored and advice on adjustments to programs and procedures are generated for EIT governance consideration.

The Transition into Operation chapter discusses both project and release management including the preparation of the environment prior promotions into production operations.

4.2.13 EIT Governance Reporting

Governance reporting keeps an eye on strategic themes, potentials for intervention on processes, and projects that are at risk, and offers opportunities for supported learning and improvement in underperforming areas. Appropriate accountability drives change and control authority and can ensure that active oversight is in place to handle possible performance penalties to third parties. Also see the Acquisition chapter.

- Build a feedback or action model to ensure that issues are addressed quickly. Review and remediation actions are authorized at the appropriate level.

- Typical EIT governance reporting consists of interval reports to C-level officers in a steering committee, oversight committee, or operations committee with measures of performance and issues from the governance management streams described in brief. Reporting at a board of directors level integrates a smaller set of measures from EIT governance.

Metrics [22] standardize the reports and allow the tracking of progress over time. Some metrics can be characterized as KPI that are of special significance to EIT and business as they are considered to best support the highest priorities.

- General themes are based on strategic plan, project, and operations demands:

- Adherence to action plan and funding

- Goal achievement measures (e.g., balanced scorecard)

- Plan execution achievement

- Organization change

- Financial position trending, demand forecast

- Outstanding work tickets

- Emergency preparedness/disaster drills results

- Quality scorecard

- All metrics should have measurable targets. There are a number of reporting approaches, with the scorecard approach being the most common. [23]

- Participant reporting from EIT areas often have more stringent targets set to ensure higher-level aggregate successful target achievement overall. Participant reporting may also combine with other lateral participant reporting metrics in an additive or algorithmic manner to construct higher-level metrics and measures.

It is becoming common for senior managers to have compensation partially or entirely driven by these performance measurement results.

5 Effective Strategy and Governance

EIT governance is effective only if cultural and management buy in are deeply established and carried on in a continuous manner to the appropriate level of management with a communication plan. However, that is not enough to ensure governance success. Reasons for ineffective governance include:

- Compliance activities and reporting without any review, action, or consequences

- Poorly designed engagement model

- Uneven authority in governance oversight

- Ineffective delegation of authority

- Untimely actioning of governance issues

- Poorly thought out governance metrics (measuring the wrong thing, or encouraging the wrong activities)

- Inaccurate data collection and spotty reporting

- Drifting from the enterprise and business strategies over time so that governance is misfocused

6 Summary

According to Michael Porter (Porter, M.E. (2008). The Five Competitive Forces That Shape Strategy. Harvard Business Review, January 2008, pp. 79–93), more than 80% of organizations do not successfully execute their business strategies. He estimates that in over 70% of these cases, the reason was not the strategy itself, but ineffective execution. Poor strategy execution is the most significant management challenge facing public and private organizations in the 21st century according to Gartner (Lapkin, Anne, & Young, Colleen M. (2011). The Management Nexus: Closing the Gap Between Strategy and Execution. Gartner). What good does it do for an organization to have a well-considered strategy that it cannot execute? Such a scenario, which is all too common according to Porter, has a dual downside. The organization will fall further behind the competition and sub-optimize resources and revenue opportunities. But that same organization will spend significant capital on failed projects that can undermine confidence with customers and investors in the management team and the organization as a whole. This is not a good position to be in and, therefore, organizations must determine effective ways to take business strategy and make it actionable.

EIT strategy determines the basic long-term goals of an enterprise. Effective EIT governance is the key to executing that EIT strategy.

Good governance is good processes and actions in making and implementing decisions. Strategy and its clear goals provide the yardstick for making decisions. Good governance has several characterisitics that underpin all of the governance areas described above. These characteristics include well-understood meeting procedures, service quality protocols, management conduct, role clarification and good working relationships, all of which contribute to the hallmarks of effective EIT governance: accountability, transparency, participation and ethical behavior.

7 Key Competence Frameworks

While many large companies have defined their own sets of skills for purposes of talent management (to recruit, retain, and further develop the highest quality staff members that they can find, afford and hire), the advancement of EIT professionalism will require common definitions of EIT skills that can be used not just across enterprises, but also across countries. We have selected 3 major sources of skill definitions. While none of them is used universally, they provide a good cross-section of options.

7.1 Skills Framework for the Information Age

The Skills Framework for the Information Age (SFIA) has defined nearly 100 skills. SFIA describes 7 levels of competency which can be applied to each skill. Not all skills, however, cover all seven levels. Some reach only partially up the seven step ladder. Others are based on mastering foundational skills, and start at the fourth or fifth level of competency. It is used in nearly 200 countries, from Britain to South Africa, South America, to the Pacific Rim, to the United States. (http://www.sfia-online.org)

SFIA skills have not yet been defined for the security chapter.

7.2 European Competency Framework

The European Union's European Competency Framework (e-CF) has 40 “competencies” and is used in the EU. (http://www.ecompetences.eu/) It uses five levels of competency. As in SFIA, not all skills are subject to all 5 levels. The EU has also created a mapping between e-CF and SFIA.

E-CF skills have not yet been defined for the security chapter.

7.3 i-Competency Dictionary

The Information Technology Promotion Agency in Japan has developed the i-CD, translated it into English, and describes it at https://www.ipa.go.jp/english/humandev/icd.html. . It is an extensive skills and tasks database, used in Japan and southeast Asian countries. Like SFIA, it establishes seven levels of competencies for skills. An example showcasing the skills and tasks relevant to this chapter is given below.

- Business architecture team — enterprise and business architecture development — business strategy and planning

- Business management team — business modeling — business change management

- Data management team data management — technical strategy and planning

- User experience team user experience evaluation — human factors

- Internal messaging team information management — information strategy

- Solution management team enterprise and business architecture development — business strategy and planning

8 Key Roles

These roles are taken from ITIL V3, 2011 edition. A good free source of ITIL V3 info is at http://wiki.en.it-processmaps.com/index.php/Main_Page.

- Enterprise Architect

- Service Portfolio Manager

- Service Catalog Manager

- Business Relationship Manager

- Financial Manager

- Availability Manager

- Capacity Manager

- Service Continuity Manager

- Risk Manager

- Supplier Manager

Other roles can include:

- Board of directors

- C-level officer

- Business partner

- Architect

- Governance body

- Regulatory authority

- Stockholder

- Vendor

9 Standards

Commonly used formal risk standards include:

- ISO 31000 2009 — Risk Management Principles and Guidelines

- ISO/IEC 31010:2009 — Risk Management — Risk Assessment Techniques

- ISO/IEC 16085:2006, System and Software Engineering — Life Cycle Management — Risk Management

- ISO/IEC 38500:2015, Information technology -- Governance of IT for the organization

10 References

[1] See also Control Objectives for Information and related Technology (COBIT).

[2] R. S. Kaplan and D. P. Norton, Strategy Maps: Converting Intangible Assets into Tangible Outcomes (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2004).

[3] www.hoshinkanripro.com.

[4] Business Motivation Model (BMM), www.omg.org/spec/BMM.

[5] A Guide to the Business Architecture Body of Knowledge (BIZBOK® Guide), Release 4.1, Glossary, Business Architecture Guild, www.businessarchitectureguild.org.

[6] Adapted in part from A Common Perspective on Enterprise Architecture, The Federation of Enterprise Architecture Professional Organizations (FEAPO), 2013, www.feapo.org.

[7] OMG Business Architecture Special Interest Group, http://bawg.omg.org, and Business Architecture Institute, www.businessarchitectureinstitute.org.

[8] A Guide to the Business Architecture Body of Knowledge (BIZBOK® Guide), Release 4.1, Section 1, Introduction, Business Architecture Guild, www.businessarchitectureguild.org.

[9] Enterprise Architecture as Strategy: Creating a Foundation for Business Execution, Peter Weill and Jeanne Ross, Harvard Business School Press, 2006.

[10] A Common Perspective on Enterprise Architecture, The Federation of Enterprise Architecture Professional Organizations (FEAPO), 2013, www.feapo.org.

[11] IT Governance: How Top Performers Manage IT Decision Rights for Superior Results, Peter Weill and Jeanne Ross, Harvard Business School Press, 2004.

[12] See also ITGC — EIT Global Controls - Global Technology Audit Guide (GTAG), Institute of Internal Auditors.

[13] See also IEEE Code of Ethics and ACM Code of Ethics and Professional Conduct as examples.

[14] See also Control Objectives for Information and related Technology (COBIT).

[15] See also DAMA-DMBOK Guide to the Data Management Body of Knowledge (DAMA-DMBOK), Chapter 4 Data Governance.

[16] See also EIT Risk Management guidance - ISACA.

[17] See also Capability Maturity Model (CMM) and Capability Maturity Model Integration (CMMI) for assessing primarily software development processes, but can be applied to other processes.

[18] Capability and Maturity Model Integration.

[19] See also Information Technology Infrastructure Library (ITIL).

[20] See also Project Management Institute, Project Management Body of Knowledge guide (PMBOK).

[21] For change management guidance — Project Management Body of Knowledge, Chapter 4 Version 5 December 31, 2012.

[22] Metric is the algorithm or mathematical and logical description of how measurement are to be taken. A measurement or measure is a score given at a point in time on that metric.

[23] R. Kaplan and D. Norton, Using the Balanced Scorecard as a Strategic Management System, July 10, 2015, https://hbr.org/2007/07/using-the-balanced-scorecard-as-a-strategic-management-system.

Also to be considered are:

- COSO 2004 — Enterprise Risk Management — Integrated Framework

- OCEG “Red Book” 2.0: 2009 — a Governance, Risk, and Compliance Capability Model

- A Risk Management Standard — IRM/Alarm/AIRMIC 2002 — developed in 2002 by the UK’s 3 main risk organizations